It is a pity for Ladakh and India that there is none to succeed Kushok Bakula Rinpoche who led the frontier region politically and spiritually for years. Let’s hope that a new Ladakhi leadership emerges

The mountainous ‘Land of the Passes’, as Ladakh is known, is celebrating the centenary of one of most illustrious sons, the 19th Kushok Bakula Rinpoche. Born on May 27, 1918, at the Royal Palace of Matho near Leh, Bakula was the youngest child of Nangwa Thayas, the King of Matho. His mother was Princess Yeshes Wangmo of the Royal House of Zangla. At a young age, he was recognised by the 13th Dalai Lama as a reincarnation of Bakula Arhat, one of the legendary 16 Arhats who were direct disciples of Gautama Buddha.

In the course of his life, Bakula had a most distinguished political and diplomatic career; ending up serving as India’s Ambassador to Mongolia where he was instrumental in reviving Buddhism. Bakula was also a member of the fourth and fifth Lok Sabha. In the early 1950s, Bakula was part of the Jammu & Kashmir Constituent Assembly representing the Ladakh region. He would often speak in favour of the integration of Jammu & Kashmir. He was proud that Jammu & Kashmir was an integral part of India: “That great country of high ideals and glorious traditions to which the nations of the world look for guidance and which is one of the potent factors for the maintenance of world peace.”

I recently came across an episode of his life which is not well-known: The Rinpoche’s visit to Tibet in 1955/56. It is particularly interesting because India faced a difficult situation after the Chinese takeover of the country, at a time when Delhi was dreaming of an eternal Hindi-Chini brotherhood. Bakula, who was then Deputy Minister for Ladakh Affairs in the Jammu & Kashmir Government, soon understood the political implications of his visit.

On November 16, 1955, Fu, the Councilor in the Chinese Embassy in Delhi walked into the South Block to discuss the Lama’s visit. He immediately asserted that China welcomed Bakula’s visit as ‘a private pilgrim’ “…therefore the Lama did not need to carry a passport or have a visa.” Fu cited the 1954 Sino-Indian agreement: “Pilgrims need not carry such documents,” he said. Fu’s interlocutor, TN Kaul, immediately saw the trick: China was not keen to acknowledge that a ‘Kashmiri’ carried an Indian passport. After a long discussion during which Kaul insisted that the trip was officially sponsored by the Indian and Jammu & Kashmir Governments, Fu had to reluctantly accept to put a stamp on Bakula’s diplomatic passport. It was the first indication of the changed situation in Tibet.

The Rinpoche was accompanied by Durga Das Khosla, an official of the Jammu & Kashmir political department, Nirmal Sinha, a scholar attached to the political officer in Sikkim and four Ladakhis, attending to the Rinpoche. At that time, India was preparing for the celebrations of Buddha Jayanti to be held the following year; it was an opportunity for Bakula to talk to Vice President Radhakrishnan, who was also the Chairman of the celebrations Committee for the Dalai Lama’s participation in the functions.

After an uneventful journey to Gangtok, the party crossed into Tibet at Nathu La on January 8, 1956. Their first encounter with the Chinese was near Chumpithang in the Chumbi Valley. Khosla, who wrote the report of their visit, complained of a ‘very surprising experience’: “When I presented my passport to the Chinese officer in charge, an interpreter who was also a Chinese, enquired from me why was I going to Lhasa. I told him that I was on duty with Kushok Bakula. He was surprised to hear this and at once retorted that Kushok Bakula was a Ladakhi, and that Ladakh being a part of Tibet, an Indian Officer could not be connected with him.” Poor Khosla had to argue at length that Ladakh was a part of Jammu & Kashmir State, to be finally allowed to proceed.

Later the sharp Jammu & Kashmir official noted: “The Chinese Government has secretly circulated a new map of Tibet among their official organisations and the pro-Chinese Institutions — in which they have shown the whole of Aksai Chin (Soda Plains) hump as a part of Tibet. Kashmir’s northern border as illustrated in this map shows some daring incursions into our Karakoram area of northern Ladakh and Baltistan.”

It was three years before the Aksai Chin issue came to Parliament and the then Prime Minister Nehru admitted that a road had been built by China on Indian soil. Khosla’s note would subsequently be dismissed, as Beijing assured Delhi that those were old maps. Bakula stayed for the next three months in Tibet; he had the opportunity to have long talks with the Panchen Lama in Shigatse, an audience with the Dalai Lama in Lhasa and could meet the who’s who in the Tibetan Capital. For the Rinpoche, who had earlier studied at Drepung, Tibet’s largest monastery, it was an opportunity to see Lhasa again after 15 years in vastly different circumstances.

On January 26, the party participated in the Republic Day celebrations at the Indian Consulate General and Bakula hoisted the National Flag: “The Maharaj Kumar of Sikkim, who was present on the occasion, also spoke a few words,” Bakula recalled.

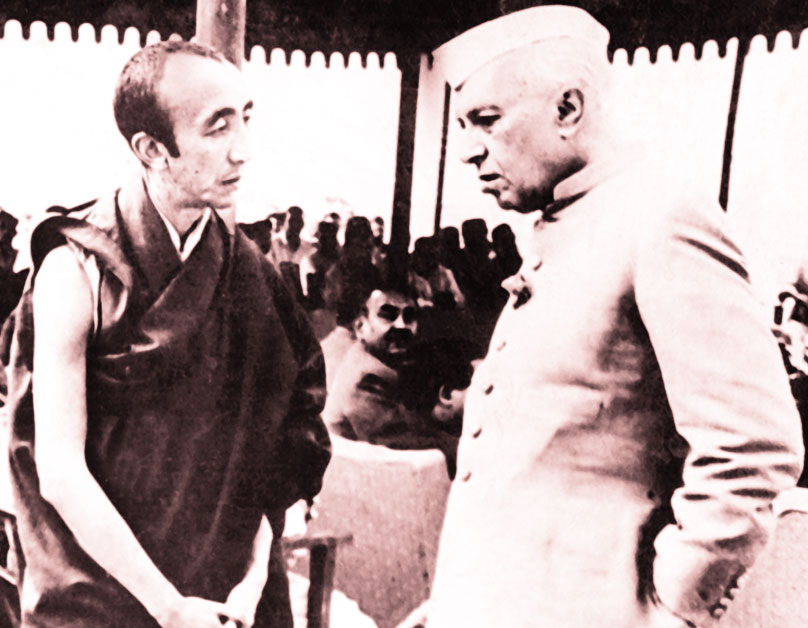

On his way back in Delhi, the Lama was received by the Prime Minister for 90 minutes and he gave Nehru a report of his tour to Tibet: “There are about 20,000 Chinese troops at present working all over the country. They build roads and buildings. A few schools for teaching Chinese and Tibetan languages have been opened at Lhasa and Shigatse. One hospital equipped with an X-Ray plant is said to have been opened at Lhasa. The Chinese at present do not interfere with the normal activities of the monasteries,” he said.

According to the Ladakhi Lama, the Chinese were going around “declaring that they will not be interested with the religious affairs of the Tibetans for times to come.” But Bakula commented: “Yet the deep-seated suspicion of the Tibetans — both lamas and laymen — against the bonafides of the Chinese people is all common and contiguous.” The Chinese did not keep their words and Delhi did not pay heed to Bakula’s warnings.

It is a pity for Ladakh and for India, that today there is no one of Bakula’s vision and capacities to politically and spiritually lead the frontier region. Even though the Dalai Lama visits Ladakh every year, it is difficult for him to defend the rights of the Ladakhis. Let us hope that a new Ladakhi leader emerges soon.

(The writer is an expert on India-China relations and an author)