Fear among Somali community compounds public health woe

Public health officials and community leaders say that even before federal immigration authorities launched a crackdown in Minneapolis, a crisis was brewing. Measles vaccination rates among the state’s large Somali community had plummeted, with the myth that the shot causes autism spreading. Not even four measles outbreaks since 2011 made a dent in the trend. But recently, immunisation advocates noted small victories, including mobile clinics and a vaccine confidence task force.

Now, with the US on the verge of losing its measles elimination status, those on the front lines of the battle against vaccine misinformation say much progress has been lost. Many residents fear leaving home at all, let alone seeking medical advice or visiting a doctor’s office. “People are worried about survival,” said nurse practitioner Munira Maalimisaq, CEO of the Inspire Change Clinic, near a Minneapolis neighbourhood where many Somalis live. “Vaccines are the last thing on people’s minds. But it is a big issue.”

A discussion group for Somali mothers at Inspire Change has shifted online indefinitely. In community WhatsApp groups and other channels, parents have more pressing priorities: Who will care for kids when they can’t go to school? In 2006, 92 per cent of Somali 2-year-olds were up-to-date on the measles vaccine, according to the Minnesota Department of Health. Today’s rate is closer to 24 per cent, according to state data. A 95 per cent rate is needed to prevent outbreaks of measles, an extremely contagious disease.

Community vaccination efforts go through cycles, Maalimisaq said, with initiatives starting and stopping. Imam Yusuf Abdulle said immigration enforcement has put everything on hold. “People are stuck in their homes, cannot go to work,” he said. “It is madness. And the last thing to think about is talking about autism, talking about childhood vaccination. Adults cannot get out of the house, forget about kids.” Vaccine misinformation has long thrived in Minnesota’s Somali community.

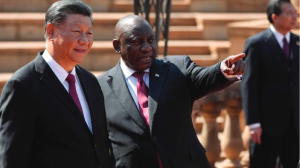

Estimated autism rates in Somali 4-year-olds are 3.5 times higher than those of white 4-year-olds in Minnesota. Researchers say they don’t know why. And in this vacuum of scientific certainty, inaccurate beliefs thrive. Many blame the measles, mumps and rubella shot — a single injection proven to safely protect against the three viruses, with the first dose recommended when children are 12 to 15 months old. Observers film while federal agents conduct immigration enforcement operations in Minneapolis.