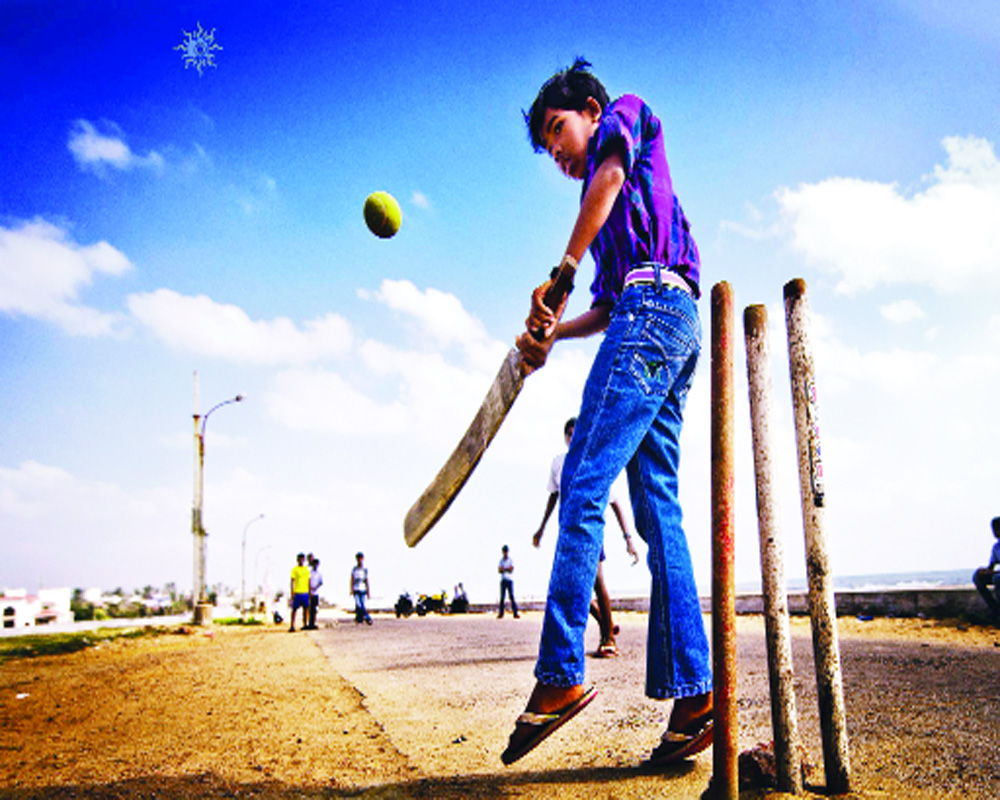

Cricket, the game of glorious uncertainties, is almost a religion in our country. It often gets more attention than other sports but then you have to play it to experience its magic

There are people who frown upon what they view as the obsessive interest that many Indians have in cricket and, to a lesser extent, soccer. One wonders how many of them are familiar with Rudyard Kipling’s reference to the “flannelled fools at the wicket or the muddied oafs at the goal” in his poem, The Islander, first published in The Times, London, on January 4, 1902. One also wonders whether even those who are familiar are aware that any attempt to cite the quote in vindication of their position, can run into a squall.

He wrote the poem in anger, as he felt that the English cricket team that was on an ashes tour of Australia in 1901-02, was getting more attention from the public than the British soldiers who were dying in the Boer War in South Africa, which was then limping towards an end. People paid lip service to their valour and “Then ye returned to your trinkets; then ye contented your souls/ With the flannelled fools at the wicket or the muddied oafs at the goals.”

It is clear from the lines that follow that Kipling’s rebuke was addressed not primarily at Britishers who played cricket and soccer but his countrymen in general for not doing enough to cope with the challenges that were going to confront the British empire—of which he was an unabashed apologist. These read, “Given to strong delusion, wholly believing a lie, / Ye saw that the land lay fenceless, and ye let the months go by/Waiting some easy wonder, hoping some saving sign/Idle—openly idle—in the lee of the forespent Line. / Idle—except for your boasting—and what is your boasting worth/If ye grudge a year of service to the lordliest life on earth?”

The reference in the last line was to conscription for military service that many in Britain abhorred. Let us, however, not digress, especially when it not even caused by “perfume from a dress”—as TS Eliot puts it in The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock. Our original concerns were cricket and soccer, to which we must now revert. I have never played much soccer. I played cricket for my College (Presidency) and clubs (Union Sporting and Dakshin Kolikata Sangsad), in Kolkata in the 1950s. Even at those levels—by no means lofty—I realised that playing required a lot of intelligence and application of mind, intense concentration, reflection, enormous will power and determination, courage, considerable physical fitness and huge reserves of stamina.

Intelligence was needed to tailor one’s batting and/or bowling to meet the demands of the pitch and the nature of the outfield, The mind had to be set to work to find out the vulnerabilities of the players of the opposing side, and devise the strategy to win a match. Determination was needed to continue fighting even when the odds were heavily loaded against one, will power to calm the butterflies that began in fluttering in one’s stomach as one walked out to bat and took guard, and courage not to run away from fast bowling on a wicket with uneven bounce where one could get hurt any moment.

The matches we played were mostly for a day. As an opening batsman, I could be at the wicket for a maximum period of three hours. As a first-change medium pacer, I bowled a maximum of eight overs in two spells. As the skipper of my college team, I fielded mostly at first slip or short square leg, which meant I did not have to do much running around. Yet I was pretty much drained out at the end of it all.

Cricket matches are war by other means among well-established rivals, and particularly so when it comes to India and Pakistan, or England and Australia for the ashes. It, however, also has other dimensions. If history, to quote TS Eliot again—this time from Gerontion—”has many cunning passages, contrived corridors,” cricket has its tantalising moments and amusing anecdotes.

Several of the latter relate to Dr WG Grace, a legend of English cricket who had an MRCS and LRCP against his name. In one of these, he had gone to a village to play in a charity match, and a massive crowd had turned out to watch. A huge cheer rent the sky as he walked to the wicket and took guard. Then the unthinkable happened. A village lad who was bowling shattered his stumps with the devil of a delivery. The umpire signalled “out.” A deadly hush fell on the ground. Grace did not move. He looked at the bowler and said, “All of these people have come to see WG Grace bat and not your monkey tricks. So go back and start bowling.”

There are stories relating to India as well. One of these is about Ganesh Bose who, along with his brother, Kartik Bose—both my maternal grand-uncles—constituted the bedrock of Bengal’s batting from the late 1920s to late 1940s. A dashing batsman, he was once out to a rank bad shot in a critical match.

One of his maternal uncles, who was among the spectators, rushed to him as he returned to the pavilion, and unleashed a mouthful of colourful abuses. Ganesh Bose glared at him for a moment and then said between his teeth, “I would have buried you here had you not been my maternal uncle (mama na hole tomake eikhane punte pheltam in Bengali).

There are many stories about Kartik Bose too.

There was a good spinner who played college and club cricket and kept long hair, which fell on his eyes every time he bowled. Watching him at the Cricket Association of Bengal’s nets at the Eden Gardens, which he conducted, Bose had asked him several times to cut his hair. As the spinner showed no sign of complying, he summoned one of Kolkata’s many roadside barbers who sat in the Kolkata Maidan, and, as the nets concluded, had a crew-cut administered to him.

I had to give up cricket shortly after 21. Those days, cricket offered neither money nor the kind of career I wanted. The crunch came when I saw some of those who played with me join the railways at subordinate levels, while my friends at college joined the Indian Railways Traffic Service and the Indian Railways Accounts Service, both central services of the Government of India, as officers.

It was a deeply painful step. My family’s link with cricket goes back to the time of Saradaranjan Ray (1858-1925), principal Metropolitan College and elder brother to my maternal great-grandfather, Upendrakishore Ray (1863-1915). A brilliant player himself and dubbed WG Grace of Bengal, he is known as the father of Bengal cricket. His grand nephew, Shivaji Ray, played for Bengal in the Ranji Trophy tournament. A person who was deeply saddened by my decision was another of my maternal grand-uncles, Prabhatranjan Ray. Very fond of me and a great supporter of my cricket, he watched every match I played.

(The author is Consulting Editor, The Pioneer. The views expressed are personal)