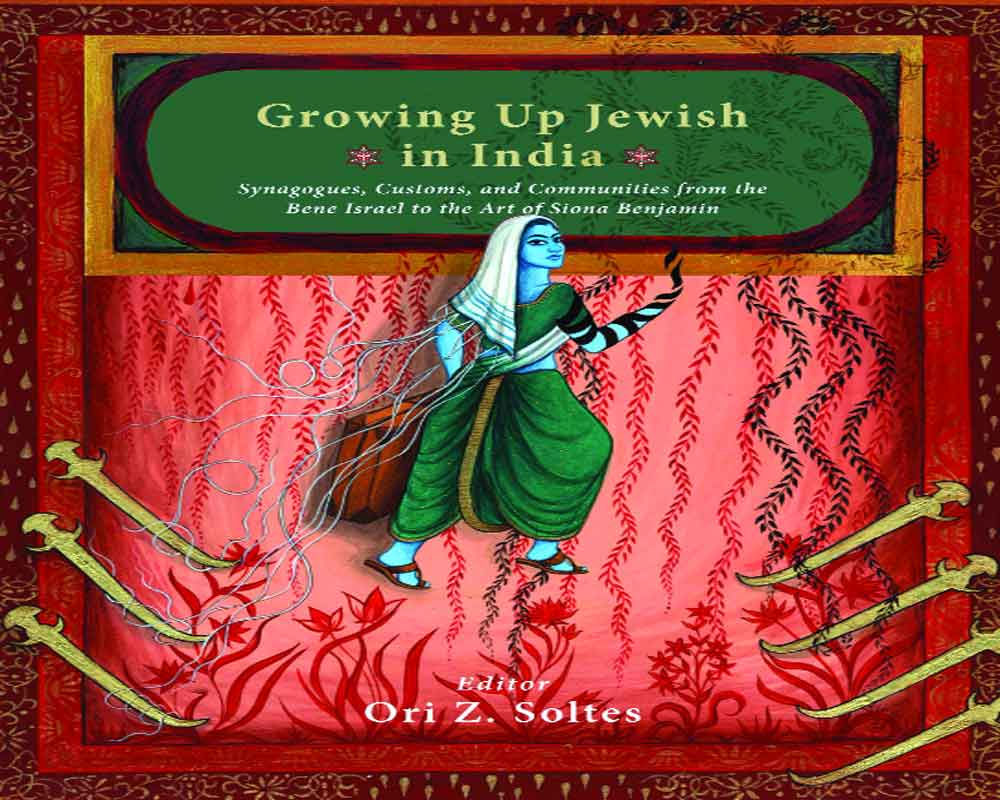

Book Name: Growing up Jewish in India

Author: Edited by Ori Z. Soltes

Publisher: Niyogi, Rs 1500

Edited by ORI Z. SOLTES, Growing Up Jewish in India is a historical account of the primary Jewish communities of India, their synagogues, and unique Indian Jewish customs. An edited excerpt:

Indian Jews have historically lived across diverse parts of the Indian subcontinent over the centuries without experiencing the sort of antiSemitism that has been so common in many other parts of the world- particularly Christian Europe, which exported its anti-Jewish sensibilities into the Muslim world eventually, particularly in the context of European colonialism and post-colonialism in the Middle East, culminating with World War I and its aftermath. Indeed, the most obvious exception to the rule of Jewish experience in India arrived with the control of Goa in the early 16th century by the Portuguese, who brought with them not only anti-Jewish feelings but the specifics associated with the development of the Spanish and Portuguese Inquisition that would affect New Christians suspected of secretly continuing to practice Judaism-and continue until the formal abolition of the Inquisition authority in 1812.

The general lack of hostility and persecution may be understood in part as a cultural phenomenon, but also as a function of the nature of Hinduism, by far the dominant religion across India, and its embrace of diverse perspectives regarding how, specifically, one might understand and address divinity. Within the singularity of Brahman-Being-what we term ‘Hinduism’ recognizes a nearly infinite possibility for divine manifestations: Brahma, Vishnu, Shiva, Devi, Krishna (and many other more minor figures) are both separate from each other and all understood to be part of each other and subsumed into a singularity that is Brahman.

Indian Jews are-obviously, by definition-both Indian and Jewish. As such, in the broadest of senses, they are part of two interwoven historical and geographical continua, each with its own unique features. India is not only a vast country with dynamic contrasts between its towering mountains and its coastal lowlands and all that lies between. It is historically complex in terms of ethnicity, religion, culture and language.

To begin with, its native Dravidian population was largely pushed to its southern climes with the arrival and expansion of the IndoEuropeans around 4,500 years ago. Among other things, this means not only that Indians fall into two very broadly different ethnic groups, but that, whereas the country is overrun by scores of different languages-23 ‘official’ languages, today, just for starters-these languages also fall into at least two very different families or categories. Thus languages like Hindi, Bengali, and Marathi are ultimately related Indo-Aryan members of the greater Indo-European family, and are largely derived from Vedic and Sanskrit (earlier and somewhat later versions of a branch of the far-flung Indo-European language family that encompasses languages from extinct Tocharian in what is now China, eastward, to Portuguese, English, and Icelandic, at the western edges of the Eurasian continent).

Conversely, languages like Tamil, Kannada, and Malayalam with an ancestry in Tamil, are part of the more geographically concentrated family of Dravidian languages. This is apart from smaller groups of AfroAsiatic and Sino-Tibetan languages-and some in the Himalayas that are still not classified. There are, overall, perhaps 415 different languages spoken in India.

India is as diverse religiously as it is linguistically. It is, as most people are aware, the country in which Hinduism was born-in fact the word ‘Hindu’ refers to the place, India, not to the form of faith. However, and more to the point, ‘Hinduism’ is also a misnomer in being used as if there is a monolithic form of faith that goes by that name, just as it is often misunderstood to be polytheistic: there are, after all, any number of gods and goddesses, it would seem, that occupy its pantheon. In truth, (to repeat), an Indian who is part of this spiritual tradition understands all of these ‘gods’ and ‘goddesses’ to be particularized manifestations of a single god of Being.

Thus ‘Hinduism’ may be understood by Westerners as a more complex version, in a sense, of Christianity in its understanding of God as triune, for instead of a threefold, Father/Son/Holy Spirit Godhead, ‘Hinduism’ offers a poly-une Brahman (Being) expressed as Brahma, Vishnu, Siva, Devi, and others. So one is typically a Saivite, say, or a Vaishnavite, believing that Siva or Vishnu represents the consummate expression of God, but embracing the legitimacy of other expressions, as well. Moreover, among the 10 avatars assumed by Vishnu over history, one of them is as a dark-skinned (blue or black) anthropomorph, Krishna, and over time, a growing community of Krishna’s followers or Krishnaites views him as the consummate manifestation of God-not as an avatar of Vishnu: on the contrary, Vishnu is viewed as a manifestation of Krishna.

Excerpted with permission from Growing up Jewish in India: Synagogues, Customs, and Communities from the Bene Israel to the Art of Siona Benjamin, edited by Ori Z. Soltes. Published by Niyogi