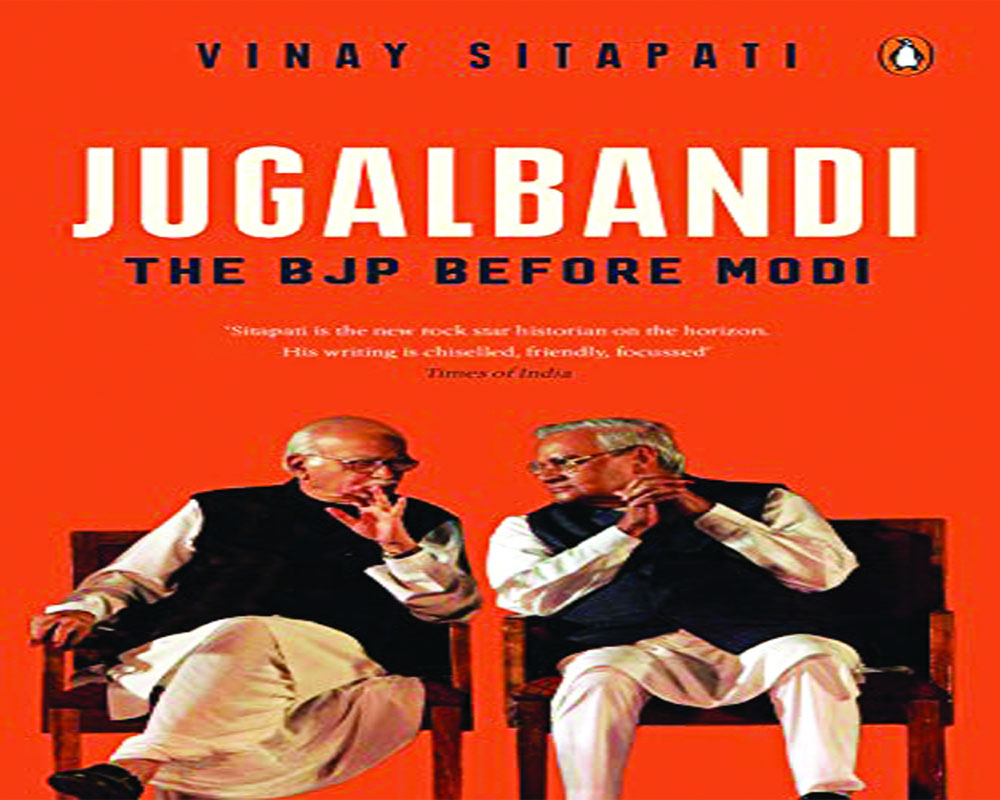

Jugalbandi: The BJP Before Modi

Author - Vinay Sitapati

Publisher - Penguin, Rs 799

The book not only provides the political account of Vajpayee and Advani, it also delicately steers through all the major events of the Indian politics, mainly right-wing, writes Mohammad Irshad

The book, Jugalbandi: The BJP before Modi by Vinay Sitapati presents a fascinating account to trace the journey of the two tallest and major drivers of the ‘India Right-wing’ as they remained at the helm and navigated through the testing times beginning from Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) to managing and executing the affairs of the Bhartiya Jan Sangh (1951) and Bhartiya Janta Party (BJP). Book offers a larger ambit to study the rise of ‘LK Advani and AB Vajpayee’ and analytical chronology of all the organisations cemented on the idea to unite Hindus that is Hindu Mahasabha, RSS (1925), Bhartiya Jan Sangh (1951), VHP (1964), BJP (1980) and Bajrang Dal (1984) and Sawdeshi Jagran Manch (1991).

Sitapati, an academic’s shadow falls over the book. He is aptly thoughtful in metaphorically chosen title; Jugalbandi — demonstrates the relationship between Vajpayee and Advani — means the melody of the ragas in Indian classical music concerts by two musicians playing different instruments, however perfectly in tune with the other. Neither of the artistes does survive under the shadow of the other, instead mutually compliment to mesmerise through that music recital. Sitapati had pitchfully utilised all the available resources, to tease out the argument to his book and left a mark of solid scholarship. It took him three straight years to complete book.

Book not only provides the political account of Vajpayee and Advani, it also delicately steers through all the major gleaning events of the India politics mainly right-wing, who have marked a substantial presence on the political map of this country. Markedly, ranging from their struggle — to register mass acceptability, electorally — prevailing in the early years of the post-independent India to the rise of bahujan politics, Khalistan movement in Punjab globalisation and Babri Masjid demolition movement. Conspicuous shift had taken place in 1980, the author says: “After decades in which Advani was subordinate to Vajpayee, by 1980 their relationship had become more equal. While Advani had always needed Vajpayee, he was now needed. They were now a classical jugalbandi.” (p 108-109) Before 1980, Vajpayee with support of Advani was busy crafting a space for himself by political burying leaders like Balraj Madhok — founded ABVP in 1948 — ML Sodhi, Nanaji Deshmukh, and others.

First chapter of the book puts light on events that caused the emergence of RSS (1925) and Hindu Mahasabha and prepares a background which helped Advani and Vajpayee joined politics with a resolve to unite the Hindus of all sects. Sitapati, theoretically spurns a widely believed argument followed after the murder of Mahatma Gandhi by Nathuram Godse, that Godse was a direct beneficiary/borrower of RSS’ religious-political ideas — on the contrary, he argues far from supporting political violence, RSS had wanted nothing to do with politics during this period (p. 33). He maintained considering Godse’s differences with RSS, Godse went on to repeatedly criticise him throughout the mid-1940s. Book detests the fact that RSS was remotely involved in the murder of the Mahatma Gandhi. This could be a matter of great further academic dispute.

Through the journey of both the leaders — nurtured by the RSS — during the formative years of the modern Indian state, book exposes the hypocrisy and inconsistency in their ideology to accomplish political goals, whether it was their shift from adopting ‘Gandhian Socialism’ to drift towards capitalism as a core economic principle and approach towards the minorities especially Muslims and Christians. Jinnah grandson, Nusli Wadia, was the first one wealthiest business person to fund the party; Bhartiya Jan Sangh (BJS) and BJP find no hesitation in accepting the donation from him. Advani perhaps paved his debt back to Nusli’s grandfather, Jinnah, — founder of Pakistan — during his visit to Pakistan and hailing him as ‘secular’, ‘Great Man’ and Apostle of ‘Hindu-Muslim Unity.’ In my reading, this ‘political jugalbandi’ was to deceptively trick non-Hindus to garner the political acceptability to further marginalise them masking their much admired fascist ambition under the garb of so called secularism followed by Vajpayee to spear the right-wing.

Jugalbandi of the Advani and Vajpayee took shape on the foundation of organisational Hindu unity and theocratic principles, meanwhile if we take to first decade of post-independent India, Jugalbandi of Nehru and Patel build on democratic-secular values, which thrive on adequate scope to diverse viewpoints, still remains as a major glue to unite the country.

In Sitapati’s argument there is a fundamental flaw, he only takes into account Vaypayee’s verbal conflict with RSS on various subjects but it largely ignores his assessment on the basis of the power and positions including prime ministership, happily cherishing on the RSS’ support in his political life, more than benefit taken by Advani, therefore Sitapati’s argument fails on merit, as Vajpayee markedly compromised on his principles in public life to peddle the idea, Right wing fundamentally stands for.

Book suggests Vaypayee’s politics was formulated during the Pt. Jawaharlal Nehru’s golden era perhaps that amplified his never ending discontent with the RSS in contrast his public political actions largely contradict Nehruvian vision except on countable occasions. For instance, after the Babri Masjid demolition, Vajpayee is famously known to be quite disturbed; however, he followed the party route and surprisingly demonstrated himself as secular leader to later siege the power in Delhi. This morally does not carry any weight as Vajpayee never distanced himself officially to fight back the unjust, inhuman and degrading ideas. It, however, will remain a perennial irony that the person who drove the rath to Ayodya to mobilise mass support in favour of the Ram Mandir, could not secure the seat of prime minister and finished in his self-nurtured party with humiliation and forced to live life in political seclusion of never fading quarters of the Lutyens Delhi.

When the right-wing could not obtain desired outcome, they tacitly decided to follow the essence of Brahman — described as absolute knowledge in Advaita vedantic philosophy — known to us as neti neti (not this, not this), similarly, without projecting a clear vision of its hierarchical and communal philosophy to gather support from all non-Hindus to establish and politically empower RSS and BJP. Neti neti, basically, here means it advocates nothing but accepts everything as long as it suits them to expand organisation, to secure the throne of Delhi, which Indian right-wing always imagined ever since its inception, to declare India as ‘Hindu Rashtra.’ Had Deendayal Upadhyay and Balraj Madhok survived strategies employed against them, we would have read their Jugalbandi.

Book seems lost in its argument as it attempts to strike a balance when two contentious historical subjects require the definite response of the author. It could be an intentional move, since the book is devoid of mere subjective convictions and prejudices as the author approaches them purely, while using considerable references.

Despite other things, it is the Hindu nationalism and call for the organisational unity that kept them together. They were devout to their ideology. At the end book, attempts to see through the new developing jugalbandi between Modi-Shah.

Book points out their similarities and dissimilarities; as new on-going jugalbandi is more hostile towards the opposition though adhere to age old conviction of public display of internal unity (p 299). New jugalbandi’s expanded social base from upper castes, to tribals, middle castes and even dalits (p 300), mastered the strategy to hide their failures by directly channelising the Hindu anger towards the Muslims on all the matters, to conveniently safeguard the ideology and galvanising the support for the larger good of Hindutva. It aims at Hindutvisation of Dalits, Advasis and OBC, this trait is a unique and distinct attribute of the Modi-Shah jugalbandi. It is authoritative, less democratic in its functioning as only the few are allowed to speak the truth to power. The Vapayee-Advani relationship was more ideological than the Modi-Shah’s relationship. But still to conclude their relationship, could be a little unfair as long as the artistes of new jugalbandi (Modi-Shah) have not gone off stage after the delivering performance.

This book engages the reader and is written sedately. Sitapati has interwoven all the major events and figures essentially required to make it an intriguing read to students of right-wing politics and post-colonial Indian Politics in general.

The reviewer is Assistant Professor, Department of Philosophy, Indraprastha College for Women, DU