Modi’s post-modern politics took root not by replacing his modernist development agenda but by working around it and mediating the universal development through particularist identities

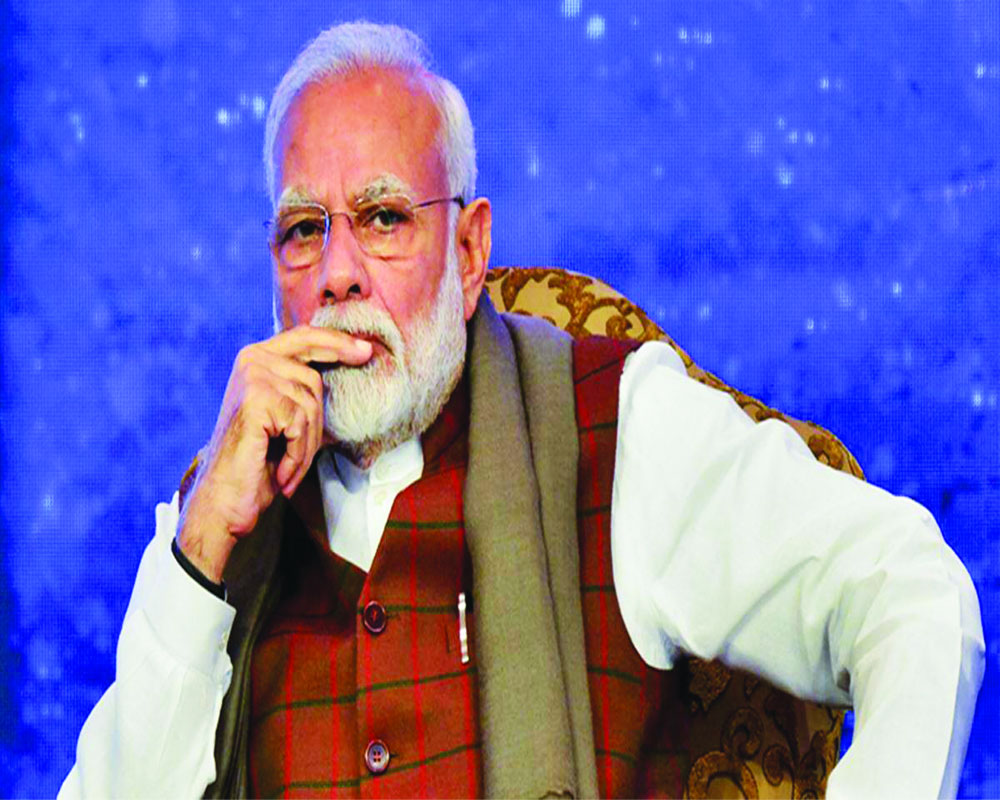

Thinking of Prime Minister Narendra Modi as a post-modernist is a little intriguing for intellectuals but a no-brainer for both, his admirers and detractors. For the former, Modi carries the hopes and aspirations of millions and there is little that he cannot do, so there is no reason why he cannot be a post-modernist. For the detractors, he epitomises everything that ails India, so it is not a stretch to assign a post-modern dimension to him. Given that the latter group has already assigned the choicest of adjectives to Modi that establish his limitless power and absolute control over the Indian body politic, they cannot deny a mere post-modernist tag to him.

That said, Modi’s supposed post-modernity may evoke surprise and even derision from the intellectual class who, for the first time, see themselves as powerless and realise that the cliché “speaking truth to power” is just an honourable trope. For them, the very idea of yoking Modi with post-modernity is an act of violence and may be a cruel joke that compromises the emancipatory promise of post-modernity and completely de-intellectualises the concept.

In fact, they could imagine this proposition as a game plan to control knowledge. Having been forced to cede political space to Modi, they had retired to their comfort zones of universities and NGOs. The possibility of Modi’s post-modernity may appear to them another strategy to rob them of their safe spaces and legitimise him intellectually.

Modernisation first: Let me assure them I have no such objective and that the present engagement comes from within the same thinking class. I would much rather identify the shift in Modi’s politics that makes his post-modernity an eminently believable idea. Before Modi became the phenomenon that he is today, he was a moderniser. After an accidental ascension to the Chief Minister’s chair, he capitalised on the entrepreneurial community of Gujaratis and channelised their success to a pan-Indian aspiration, to be known as the “Gujarat model”, though critics would still find many contradictions within that claim.

In terms of Hindu consolidation against an aggressive Mandalisation of politics and the division of Hindu society along caste lines, BJP veteran leader LK Advani had already sought to unify Hindus through the Ram Mandir agitation. Modi took this unification strategy from Advani and gave it a developmental idiom. Whether it was intended to arrest the fragmentation of Hindus for cultural or political reasons is anybody’s guess, but what we can agree on is the fact that Modi went beyond Hindu unity and created a developmental unity.

As a modernist he was both, disruptive in terms of breaking away from traditional politics and constructive, as in ushering in a new type of politics that was the beginning of development. His modernity was palpable when he invested his political future in the idea of development as universal with the hope of neutralising particularist assertions.

If secularism was the master code of the pre-Modi era, his counter master narrative was development. The slogan “Sabka Saath, Sabka Vikas, Sabka Vishwas’’ articulated a new India’s resolve for the 21st century. This is not to gloss over alleged incidents of atrocities against minorities after his rise as Prime Minister, though they are not unique to his era. As Chief Minister, Modi had shown his resolve in infrastructure development, even by demolishing many Hindu temples in Gujarat’s Capital Gandhinagar.

Modi took upon himself the responsibility of creating a new political culture where nationalism is no longer a bad word and development is the master legitimator of contemporary politics. His rationalisation of development as the new mantra may be dismissed as reflective of a post-World War mentality but the fact that India continues to be underdeveloped is the reason behind Modi’s success as a moderniser. His promotion of women’s empowerment (through the ‘Beti Bachao, Beti Padhao’ initiative), more seats for women candidates in IITs and the ‘Ujjwala Yojana’ for rural women, among others, created development as the new universal and legitimated development as the new catch-all category of Indian politics. So much so that all parties reimagined themselves as development-oriented ones.

The post-modern turn: The Opposition had understood that to keep their hopes alive they had to reclaim Backward communities from Modi and bring them to make common cause with minorities. The fact that non-BJP parties had benefitted heavily from this so-called Backward-Dalit-Muslim unity, something which development started eroding steadily, made them jittery.

Theirs was a post-modern challenge that survived on dissociating Dalits, OBCs, women, Muslims from the modernist project of development. Modi needed a new strategy to reinvent himself and he found one, to beat his critics in their own game. His modernist thrust had created a catch-all and all-encompassing category such as development that appeared to have replaced politics. Now began Modi’s post-modern politics, not by replacing his modernist development agenda but by working around it and mediating the universal development through particularist identities.

The mistake many intellectuals make is imagining that Modi and his party as intellectually challenged. They too, imagined the strategy of fragmentation as the bulwark against Modi’s juggernaut (that depended on universals such as nationalism and development) and highlighted difference, fragmentation, particularism and so on. If Modi spoke of Hindutva, the post-modern impulse was to highlight caste difference; if he spoke of nationalism, the post-modern impulse was to offer regional and religious challenge; if development promised equal opportunity, the post-modern alternative was to highlight development’s religious and caste blindness. Modi used their tool of fragmentation to fragment further.

Most politicians and intellectuals were convinced that particulars such as Dalit or Muslim or Other Backward Classes (OBC) can never be another universal, but Modi knew better. He criminalised triple talaq and broke the Muslim universal and its inherent patriarchy, something that had been avoided by most political parties.

The Mandalisation of politics had created the greatest monolith of OBCs but Modi knew that OBC is a political construct and so can be refashioned. More than 50 per cent of the country’s population cannot be a monolith and that it cannot be a cohesive unit. In 2018, the Rohini Commission recommended splitting of the OBC quota of 27 per cent because about 25 per cent of the 27 per cent OBC quota is usually gobbled up by around 10 dominant castes and the remaining 1,000 castes are largely left out. Modi instinctively understood that these silent groups can be persuaded to see the irony of OBC reservation and can be the site of a counter-OBC formation.

He also worked around the creamy layer among the OBCs (mostly the salaried and middle-class) who are usually vocal about rights. He knew that their exclusion from the OBC umbrella would dilute the narrative of OBC assertion. So far as Dalit votes are concerned, every State has a few dominant castes (Jatavs, Mahars, Madigas depending on the region) who are heavily politicised to the extent of hijacking the Dalit movement away from marginal Dalit communities.

Now Modi and the BJP are actively working with these marginalised castes and are integrating their practices in the Hindu cultural sphere. They are also actively empowering them through mobilisation at the grassroots level.

Conclusion: Mandal politics had politicised a few dominant castes. Modi is taking it to its logical conclusion by breaking the monolith. Similarly, the single voting block of Dalits is over and politicians and intellectuals cannot complain against something that they themselves championed. On top of that, Modi’s introduction of the Economically Weaker Section quota was a masterstroke that brought class rather than caste into distributive politics, something Indian communists had chosen to ignore.

Intellectuals and politicians did not have the foresight to see the vulnerability of their position. In their enthusiasm, they had forgotten that though the minority/Dalit/OBC difference can threaten the universal nation, the former is equally vulnerable to contradictions within. Modi beat them in their post-modern game.

(The writer is Professor, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, IIT Madras and a cultural critic. The views expressed are personal)