Quality education and initiatives like Right to Education Act are fine but they are incomplete without competent and qualified teachers, something he emphasised

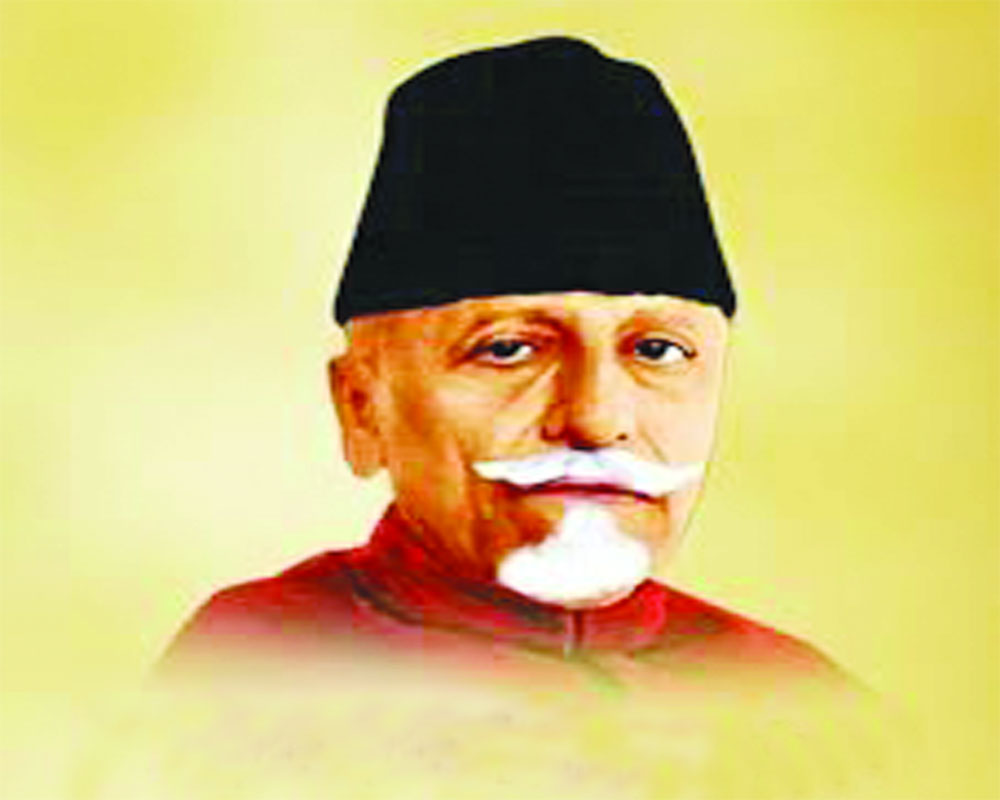

India celebrates its National Education Day on November 11, the birth anniversary of Maulana Abul Kalam Azad — a great scholar, freedom fighter, politician and a firm believer in the unity of India — but do we honour his passion and ideals? Azad is also remembered as our first Education Minister. Born in Mecca in 1888, his family moved to Kolkata in 1890. He was self-taught and never went to school. He started teaching at the age of 16 and continued his scholarly pursuits even while in the thick of national politics. He wrote poetry, translated the Quran and even authored several books.

Young Azad was influenced by revolutionaries and was deeply impressed by Sri Aurobindo. In 1908, he visited Iraq, Egypt, Syria and Turkey and was pained to find that while in these countries Muslims were fighting for freedom and democracy, Indian Muslims were favouring the British, keeping away from the nationalist movement. To change the Muslim mindset, he started a journal, Al-Hilal, in July 1912. He joined the Indian National Congress and became its president in 1923 at the age of 35. After the two-nation theory and the demand for a separate nation for Muslims gained ground, Azad could envision its conceptual fragility and disastrous future consequences for the nation, particularly for the Muslims. Unfortunately, India was partitioned and even Mahatma Gandhi and Azad had to become a party to it. What followed at the time of the Partition and the near permanency of the India-Pakistan conflict clearly indicate how sound and pragmatic ideas are sometimes lost in the political arena, resulting in unimaginable damage to future generations. Both India and Pakistan are perpetual victims of this scar.

Pakistan — fully submerged in religious orthodoxy and ignorance — inflicted several self-destructive wounds, suffered a couple of humiliating military defeats and was even decimated. It is propagating worldwide terrorism, and ironically, suffering its venomous consequences as well. Azad and Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan are two outstanding luminaries of the freedom struggle, who presented the real — liberal and dynamic — version of Islam before their countrymen. Had the Muslim community paid heed to them, the world would not have been put under debilitating violence, insecurity and distrust that have engulfed humanity today.

The recent murderous attacks in France have stirred diametrically opposite reactions, indicating how serious the issues of religious bigotry, blind fundamentalism, terrorism and global insecurity are. The only ray of hope lies in education, formal education of the young and simultaneously the education of people in positions of power and decision-making in their “trusteeship role” for the generations ahead.

This year, the National Education Day celebration could very well focus on the role of education in achieving social cohesion and religious harmony. The recently launched National Education Policy 2020 (NEP) has considerable connect with the basic principles of Buniyadi Talim, which was proposed by Gandhi in 1937. Delivering the presidential speech at the fourth session of the Central Advisory Board of Education (CABE) on January 13, 1948, Azad, the then Education Minister, said: “In connection with the scheme of basic education, the question of religious instruction had cropped up at that time. Two committees of the board pondered over it but they were unable to come to an agreed decision. I should like this question to be reconsidered in the light of the changed circumstances. For our country, this question has a special meaning.”

A realistic comprehension of the spirit and intent of Buniyadi Talim was indeed missed by those under the influence of “all that was Western and British.” To them, the existing transplanted system was doing fine. So why disturb it? It is only now that the consequences of this approach are before us: Unemployment, poverty, hunger, internal migration, neglect of villages and farmers and much more.

Everyone talks of a lack of moral, ethical and humanistic values. Corruption is a consequence of diminishing emphasis on character-building. Luminaries like Azad had anticipated such concerns. After posing the problem and putting it in the context, Azad articulated its elements: “It is already known to you that the 19th century liberal point of view concerning the imparting of religious education has already lost weight. Even after World War I, a new approach had begun to assert itself and the intellectual revolution brought about in the wake of World War II has given it a decisive shape. At first, it was considered that religions would stand in the way of free intellectual development of a child but now it has been admitted that religious education cannot altogether be dispensed with. If national education was devoid of this element, there would be no appreciation of moral values or moulding of character on human lines. It must be known to you that Russia had to give up its ideology during the last World War. The British Government in England also had to amend its education system in 1944.” With a crystal clear comprehension, Azad was convinced that the West felt the need of religious education as without religious influences, people become “over-rationalistic.”

In India, we are surrounded by “over religiosity.” How secularism is being interpreted in India leaves much to be desired, clarified and comprehended to bring people of varied religious affiliations to accept the equality of all religions: “Ekam sat viprah Bahudha Vadanti” (There is only one truth, learned ones call it by various names). What Azad articulated in the meeting on education has a global contemporary relevance: “Our present difficulties, unlike those of Europe, are not creations of materialistic zealots but of religious fanatics. If we want to overcome them, the solution lies not in rejecting religious instruction in elementary stages but in imparting sound and healthy religious education under our direct supervision so that misguided credulism may not affect children in their plastic age.”

Azad was India’s Education Minister for about a decade. His concern on the issue of religious instruction indicates his seriousness on social cohesion, religious amity, unity and integrity of the country, and that all of these depend on the right approach to education in human values and continued insistence on character formation. He was convinced that Indians would like their children to get religious education. If the State refused, they would do so privately. He was concerned that private sources were already working and were entrusting religious education to those teachers “who though literate are not educated. To them, religion means nothing but bigotry.” To save the “intellectual life of our country,” Azad emphatically warned all concerned not to entrust the imparting of early religious education to private sources. Further, no national Government could shirk the responsibility of moulding the “growing minds of the nation on the right lines” as it is its primary duty.

Here, Azad offers a global education policy guideline: Imparting quality education and initiatives like Right to Education Act are fine but these remain incomplete without a clear mention that such education shall be provided only by competent and qualified teachers. Further, nothing that distorts the sensitive young minds in any way shall be allowed to permeate the educational endeavour.

Education must be free from vested interests that believe in the supremacy of any single religion, which does not subscribe to the equality of all religions and refuses to introduce transparency in their schools — in approach, content and pedagogy.

It is well-known that schools of certain denominations are not preparing children for a world of peace and tranquility, for acceptance of diversity, for social cohesion and religious amity. And it is not a new phenomenon, as would be clear from Azad’s description given over 72 years: “The method of education, too, is such in which there is no scope for a broad and liberal outlook. It is quite plain, then, that the children will not be able to drive out the ideas infused into them in their early stage, whatever modern education may be given to them at a later stage.” At this stage, it is a global phenomenon that terrorist and fundamentalist organisations suffer no dearth of highly educated and technically qualified and competent young people.

The implementation of the NEP 2020 has begun in earnest. The growth, progress and development of India would depend on the quality of its education and the level of social cohesion and religious unity, seeds of which are to be sown in its schools, classrooms and playgrounds. The NEP 2020 must equip every Indian to stand up and repeat with full conviction what Azad had declared in 1940: “I am part of this indivisible unity that is Indian nationality. I am indispensable to the noble edifice and without me this splendid structure of India is incomplete. I am an essential element which has gone to build India. I can never surrender this claim.”

The great visionary paved the path for every Indian to move ahead and in the process made a singular contribution in the human march towards a world of peace, non-violence and love.

(The writer works in education and social cohesion)