For the foreign traveller, the new India, as opposed to the one in guidebooks, has been difficult to reconcile with. That’s costing us business and perception

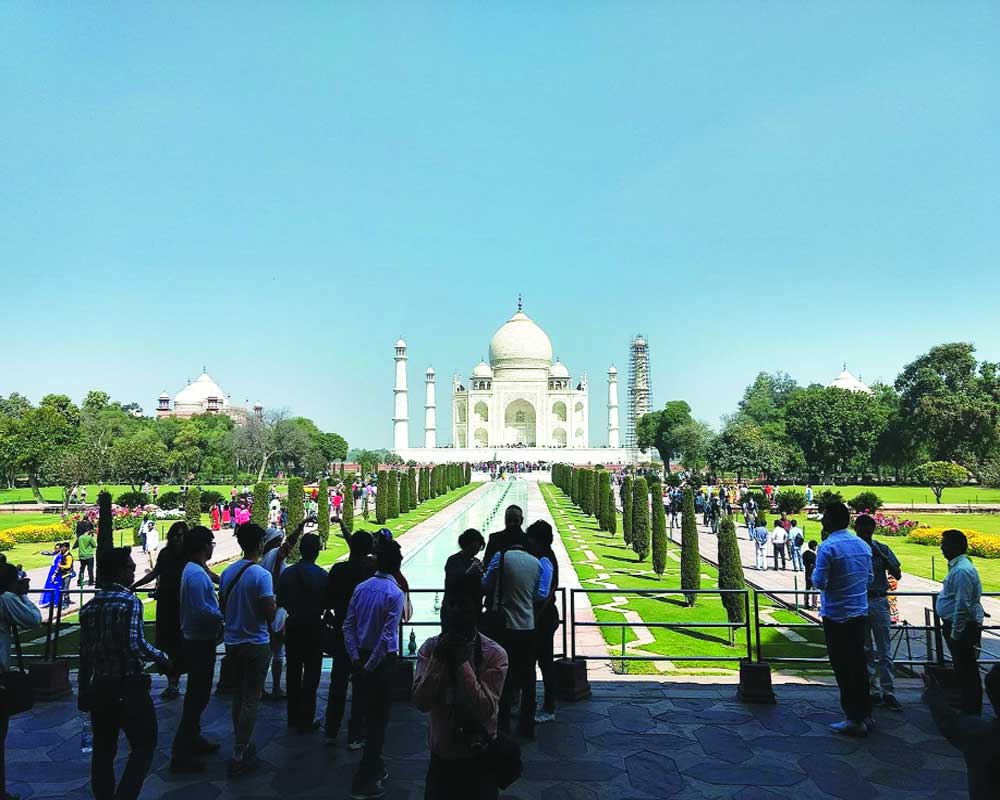

An 1899 handbook on the Taj Mahal had said that your presence at the monument was enough to make the whole world your kin. No matter what the asymmetry of cultures, the pristine symmetry of the structure and its elevated consciousness by the banks of the Yamuna seem to clear all the cobwebs of our minds into an incredible whiteness of perfection. The Taj has withstood many assaults in its time — physical, cultural and ideological. Now it has even learnt to live in splendid isolation like its creator and Mughal emperor Shah Jahan, held captive by the circumstances of our time.

I happened to be in Agra over the Christmas/New Year weekend quite by chance, it being the celebratory time of the year when a record number of tourists congregate for a pilgrimage of sorts to witness the world’s wonder but perhaps for the first time felt unwelcome in a city under siege. The administration, fearing tension following the protests over the Government’s new identity-based and divisive policies, had ensured a virtual lockdown with internet shutdowns, restricted entry, limited mobile telephony, barricaded localities and chaperoned access. Agra has not just been any other tourist town; it has been the crown of India’s Golden Triangle, our most popular circuit, where heritage is living, the entirety of its local economy and identity geared around its sense of hospitality. While the Taj has been the pivot of the tourist economy, the attention span it commands has seldom extended to other structures. Over long years, successive Governments, culture czars and tour operators have painstakingly worked on “Taj by moonlight” sightings, cultural soirees, art walks, crafts workshops on pietra dura (the inlay work used in the monument) Mughal spas and a host of other experientials to hold the tourist. Though middle India sleeps early, the tourist enclaves have always bustled with life and danced to an eclectic vibe. The jackboots not only destroyed that spirit but years of hard work to make the tourist stay in the city and not run after the customary ritual of a day trip.

The desolateness echoed everywhere. Shops in the Taj complex itself downed shutters as many of their owners could not make it past “troublesome” localities without being asked why they needed to move outdoors in the first place. The little that did open for business wound up early because the business was not worth the establishment cost; there weren’t enough tourists going around. On Christmas day, the Taj had the highest number of visitors this season, which was dismally low, less than half of what the monument gets on that day every year. Tourist operators have been conservative in estimating a 40 per cent drop in business. But unofficially, fearing stricter gag orders, they tell you that business has fallen by 80 per cent, the food business being hit the most severely. Cafes, proudly displaying free wi-fi, an attraction for young travellers on the move, looked bleak. Many of them told us that the administration had really nothing to fear as no rioting of consequence had taken place in the city. Neither would it be as even the most ghettoised Muslim had been tamed into submission by the brutal face of organised repression and random pick-ups of innocents, simply because they “looked” suspicious. In fact, they did not want any activist to take up their cause, fearing a hitback. But the fear psychosis and aura of a police state was chillier than the December cold, the face of the policeman more ominous with the temporary power he had been given to intimidate people, who wouldn’t have noticed him otherwise. The friendly tourist police shut shop earlier than usual, handing over charge to the special personnel on the ground. The unsaid dystopian future was suddenly all too palpable.

It all began with the site. Much time was lost because of the elaborate entrance drill through circuitous pathways and one-man pass-throughs — something which was most inconvenient to the elderly and the wheelchair-bound — and being herded by the sternest minders. The Taj terrace had more security personnel than tourists, who were being escorted in batches. Low turnouts meant fewer battery-operated carts and buses were available for ferrying visitors, most of whom were left waiting endlessly. And as the fog rushed in from the edges post-sunset, the Taj tourist complex crawled with military police. Café El Clasico, which serves light bites and beams European football alongside, was empty. We were the third or fourth visitor group it had got that day. The internet shutdown meant no online bookings or transactions could go through, no aggregator service, be it of food or transport, was operable, no apps were serviceable and no video chats were possible. Agra that weekend had stranded tourists on the move, who completely rely on online reservations and forward linkages to plan their holidays. Hotels were no better. The broadband worked late evening at some properties in fits and starts, with ridiculously low speeds. Cable TV was down, too, and where available, offered you more free-to-air entertainment channels than credible news. Why would anybody want news on a holiday? Apart from “our” kind. What about telemedicine networks and online referrals at hospitals then? Or even hotels themselves, which were off the grid for prime bookings? Agra hotels were not only lowering tariffs but even encouraging tourists to stay an extra day with complimentary benefits to ensure occupancy figures. Understandable as internet blackouts had meant a 60 per cent drop in December bookings, according to operators. Over 200,000 domestic and international tourists had either cancelled or postponed their trip to the Taj in the last fortnight of 2019.

The arrogance of power and machismo may seem the new normal but international travellers, who are our actual brand ambassadors, have clearly been shocked by the new idea of India as opposed to the one depicted in guidebooks. Many were cautious about talking, fearing they would be unnecessarily harassed or sent back. Everybody was aware about the deportation of the German IITian and the Norwegian student for sympathising with and extending moral support to the protesters. Their concerns are deeply problematic for us because for the first time they felt there were no shared values of democracy here anymore. Those drawn by the mysticism of the Orient wondered how India, as an ancient civilisation that had absorbed millennial layers of influences through the Silk and Spice routes but still held its own, could disown its ethos of inclusivity and subscribe to alien ideas of isolationism and racism? Some said they respected India for making feel everyone at home no matter what the shortcomings, simply because it was not like China. “Even there, the autocracy of the State doesn’t feel as overbearing. Yes they watch the tourist districts but within their orchestrated confines, they do not dilute the overall experience,” said one of the travellers. Another cancelled his visit to Varanasi and decided to return to Delhi the next morning. Others cut short their trips following travel advisories from their countries. Cancellations are bad news for hoteliers during the busiest time of the year. Worst, European travellers, who have been born of the colonial legacy and have an unexplained happy feeling about coming to India and embracing it with its warts and eccentricities, are going back disturbed. Simply because the India in their genes is not the India today. Much like author William Dalrymple, who had never thought of leaving India but is wondering whether he should die here or not. Dangerously, some even asked if the clampdown had anything to do with eroding Mughal legacies and their significance. Nobody dare ask an Indian this question but seen in the context of Chief Minister Yogi Adiyanath’s earlier statement that the Taj was not that important a monument, one can understand why it is being raised in the first place.

No regime, no matter what its colour of politics, can disregard the economic value of the Taj. Especially, when Prime Minister Narendra Modi himself has pitched tourism as the key growth driver of a slowing economy. Government records show that Mughal era monuments attract the highest number of tourists and the Taj Mahal generates the maximum revenue. It attracts over 6.5 million tourists every year, generating nearly $14 million annually from entrance fees. And spends on its maintenance have remained almost the same in the Modi years because of its economic and metaphorical value. But has the venom of politics stained its walls deeper this time? Politicians would tell you otherwise but the truth emerged at the twilight hour. As the Taj darkened its silhouette with the receding light of day, a small temple behind it on the river bank came alive with bells and fire rituals. The birds came home to roost on the domes, lulled by the dulcet beats. The Ganga-Jamuni tehzeeb can still withstand a rough tide or two.

(The writer is Associate Editor, The Pioneer)