With his multi-layered narrative techniques, Kedarnath chose to write about the inescapable predicament of the post-independent nation which encouraged and even compelled young aspirational minds to go far from their rural, cultural backgrounds

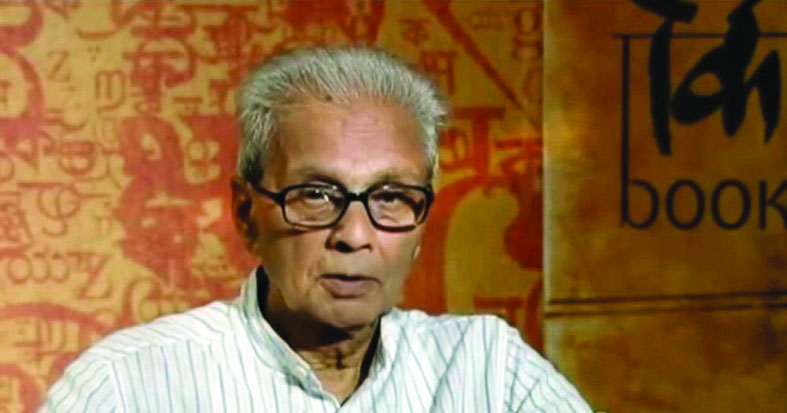

Even before Kedarnath Singh was conferred the Jnanpith Award in 2013, he enjoyed tremendous critical acclaim as a phenomenal Hindi poet who was favourably compared with some of the major contemporary Indian poets. The highest literary prize was in a way an attestation and confirmation of the fact that he had attained the status of a kind of cult poet for about a decade.

His classmate, a well-known Hindi writer, Vishwanath Tripathy, mentioned that Singh became popular from the Intermediate class itself. People used to praise him a lot and he was often discussed by his fellow students like a famous poet. A major Hindi poet, Manglesh Dabral, reinforced this perception and added that only Baba Nagarjun can be said to be more popular a poet than Kedarnath Singh.

As a matter of fact, Singh was not only popular but also a successful poet who received the Kumaran Asan Award in 1980, and the Sahitya Academy Award in 1989. In addition to the above prizes, he was also honoured with many other awards that were given by literary organisations from different States, such as Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh and Odisha. He also had the distinction of being a fellow at the Sahitya Academy, which is usually considered to be the greatest honour available to a creative writer in our country.

Otherwise deeply divided in their conceptualisation of the very idea of literature and, in turn, canon formation, Hindi poets belonging to both the progressive (pragatavadi) and modernist (prayogvadi) persuasions, had not just identical appreciation for his poetic endeavours, but also preferred to put him on a high literary pedestal. They are known to have come together for throwing such accolades before the way of only two other modern Hindi poets — Gajanan Madhav Muktibodh and Shamsher Bahadur Singh.

Ever since the highly influential Hindi writer, Sachchidananda Hirananda Vatsyayan, popularly known by his pen-name ‘Agyeya’, identified the poetic talent of young Kedarnath Singh in 1953, and chose to publish his poems in his prestigious journal, Prateek when the latter was only 19-year-old, and later included him in his canonical anthology, Teesra Saptak, Singh emerged as a wonderful poet.

Singh almost equally wonderfully charted an impressive poetic trajectory during his five-decade-long literary journey. He published as many as eight volumes of immensely engaging poetry written with a distinctly different sensibility from what we witnessed in the preceding Chhayavadi poetry and with a more complex and remarkably consistent but independent poetic vision than we find even amongst many of his younger and elder contemporaries.

It is often argued that Trilochan Shastri, an elder contemporary poet who had begun to explore the common concerns of the ordinary people much earlier along the lines suggested by the Pragatavadi thought, generated a great deal of influence early on the way Singh began to conceptualise the idea of a poet. Many readers emphasise that the radical poet, Pablo Neruda, and the French surrealist poet, Paul Eluard, made a greater impact on the making of Singh’s poetic sensibility.

Some discerning voices firmly believe that Singh eventually succeeded in his efforts to develop an effective and independent artistic framework which enabled his rural experiences to sit comfortably side by side with his sophisticated urban outlook. It helped him establish a harmonious confluence between his refined poetic diction and stunningly unconventional images, and equipped him to put together in a productive way an alert, direct poetic voice with an apparently detached kind of poetic contemplation so as to strike a fine balance between the pulls of modernist tendencies and the pressures of indigenous sensitivities.

But a careful, critical look at his inextricably intertwined personal and poetic journey tells us a different story altogether. Singh had an undying attachment for his village, Chakiya, where he was born and which is situated in the Balia district of Uttar Pradesh. His rural upbringing allowed him to indulge in swimming for hours and climbing trees as a matter of routine. Like villagers of his generation, he loved walking barefoot and speaking Bhojpuri. Moreover, he used to thoroughly enjoy the delightful stories told by his grandmother from the maternal side, and also those interesting songs that women of his village preferred to sing in the early hours in honour of the mother Ganga.

In fact, the river Ganga runs just three kilometers away from his village, so does river Sarayu. The former flows to the south of the village and the latter to the north. For Singh, it is indeed the rivers that made him aware of the presence of nature whose influence remained undiminished for the entire life.

When he left his village for Varanasi, where he studied first at Uday Pratap Intermediate College and then at the Banaras Hindu University (BHU), Singh discovered a new world which opened up newer opportunities for his academic and artistic development. College enabled him to hear poems from the veteran poets themselves, like Ramdhari Singh Dinkar and Harivansh Rai Bachchan, and in some way encouraged him to begin writing poetry, that he eventually did.

And then he happened to meet his mentor, Trilochan Shastri, a Pragatavadi poet who had already revolutionised Hindi poetry by introducing democratic and radical contents in his very first collection of poems, Dharati (Earth).

At BHU, he had the privilege of being taught by the legendary teacher, Hazari Prasad Dwivedi, who helped him shape his creative sensibility in a significant way. Academic atmosphere of the university offered him opportunities to listen to the distinguished scholars from both India and abroad.

After finishing his studies at Varanasi, where he stayed for about 17 years, his job brought him to an utterly backward place called Padrauna where he worked till he moved to New Delhi when he was appointed as professor of Hindi at the Jawaharlal Nehru University. He was charmed by the creatively fertile environment of the university campus which provided him a platform to refine his poetic skills, which, however, beautifully did embody from the very beginning those realities that kept unfolding in his immediate surroundings as well as in the distant places.

Despite the fact that circumstances compelled him to physically disconnect with rustic roots, he never ever lost sight of their importance, and also that of his relationship with nature, Bhojpuri bhasa and rural people, such as carpenter, tailor and weaver and others like them.

A characteristic example can be seen in the embodiment of uneasiness and enduring tension between the rural and urban mindset which is pretty much evident from the poet’s persistent anxiety about the presence of a kudal (spade) in the drawing room of a metropolitan city like Delhi. In fact, his poetic endeavours can best be understood and interpreted in terms of his consistent engagement with as realistic a representation as possible of the emergent socio-political and cultural conditions in different parts of the nation where he underwent the kind of experiences that a great majority of his compatriots were simultaneously undergoing.

It is precisely such a serious preoccupation with the post-colonial conditions of the country for the sake of giving them a vivid expression in his poetic compositions that primarily defines Singh as a quintessentially post-colonial poet. He chose to narrate with his multi-layered narrative techniques the inescapable predicament of the post-independent nation which encouraged and even compelled young aspirational minds to go far away from their rural, cultural backgrounds that they nonetheless could not afford to forget and indeed kept longing for the rest of their lives.

This is the personal dilemma of the poet himself. But it is the collective dilemma of post-colonial India too. This historical predicament makes our chances of upward mobility in life almost entirely dependent on a definite disconnection, a sort of rupture with our nourishing roots in order to often preempt the possibilities of a genuinely satisfying existence so evocatively articulated in the following lines: “My home is/Where we witness tremendous cry”.

We all can only aspire as the poet does in his representative poem, Haath (hands): “While holding her hands/ Into mine/ I thought / The world should be as pretty and warm/As hers.” Such aspirations for a better and beautiful world embodies the undercurrents of disappointing, rather disturbing post-colonial moments which constitute an indispensable part of the creative consciousness of an enormously cultivated poet with a fiercely independent post-colonial mind.

(The writer is Assistant Professor of English at Rajdhani College, Delhi University)