Both politicians and journalists risk misjudgment when they distance themselves from the realities on the ground

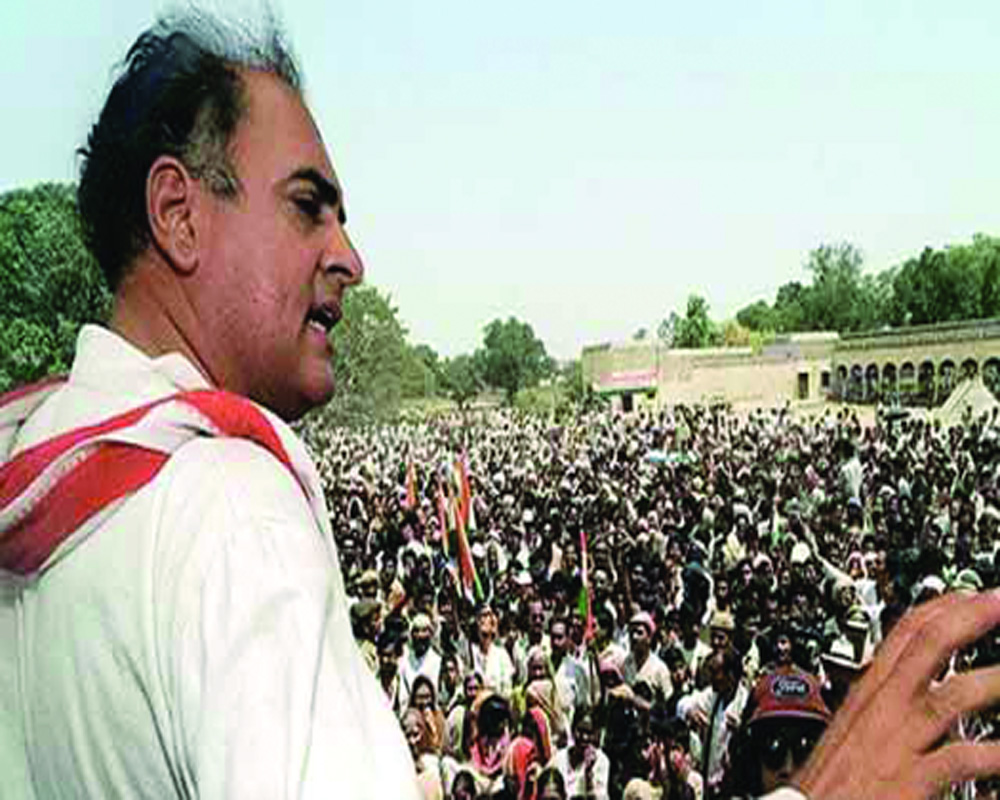

The 1984 election results were a shock to many. Rajiv Gandhi won a record-breaking 414 seats, toppling major political figures. Veteran leaders like Atal Bihari Vajpayee and Chandra Shekhar faced unexpected defeats—Vajpayee in Gwalior and Chandra Shekhar in Ballia. But this story is less about the triumphs or losses and more about a crucial lesson this journalist learned from an open-hearted conversation with Chandra Shekhar.

In an interview, this journalist asked the seasoned leader if he had anticipated the wave that swept away even stalwarts like himself. Chandra

Shekhar replied candidly: “To be honest, I had become disconnected from the grass roots. I didn’t realise there was such a wave.” This realisation left a lasting impact on the journalist, shaping their perspective going forward.

The same kind of shock had reverberated through the nation during the 1977 elections, but in the opposite direction. Indira Gandhi was ousted from power, losing her own seat in Rae Bareilly, while her son Sanjay Gandhi lost in Amethi.

The Congress party was routed, failing to win a single seat in Uttar Pradesh or Bihar. Despite her stature and the counsel of her closest advisors, Indira Gandhi had also become detached from grassroots sentiment.

This disconnect was something this journalist later witnessed in the field of journalism itself. During the 1984 anti-Sikh riots, this journalist returned from the field after witnessing the violence firsthand.

His editor, Ayub Syed, was discussing the events with a senior journalist, OP Sabherwal, who was analysing the riots from afar. Sabherwal likened the situation to 1947, predicting that the riots would continue indefinitely.

The journalist respectfully intervened, sharing what he had observed in RK Puram: a Gurdwara under attack, granthis being rescued by the army, looters scattering when a single soldier raised his hand, and a crowd dispersing with just a shout. He explained to his seniors that the violence was being stoked by the Congress government, with rioters emboldened by police assurances of impunity.

The journalist conveyed that the riots were far from uncontrollable and could be stopped whenever the government chose. And he was proven right; the violence ceased once the government decided it had gone too far.

The lasting lesson? Whether a politician or a journalist, detachment from reality clouds judgment. Without a connection to the ground, even the most obvious forces at play can go unseen.

The 1984 election and subsequent events taught a vital lesson about staying connected to the grassroots. Rajiv Gandhi’s landslide victory, which swept aside prominent leaders like Atal Bihari Vajpayee and Chandra Shekhar, highlighted how even seasoned politicians could lose touch with public sentiment.

In a candid interview, Chandra Shekhar admitted his own disconnect from the grassroots, mirroring the misjudgment that cost Indira Gandhi the 1977 election. This theme resonated again during the 1984 anti-Sikh riots, where a journalist’s firsthand observations clashed with distant analyses in the newsroom. The violence, stirred by political agendas, was ultimately controllable when authorities chose to act.

The takeaway? For both politicians and journalists, a disconnect from on-the-ground realities can obscure clear judgment, leaving critical forces unrecognised. Staying rooted is essential to understanding and addressing the true dynamics at play in any situation.

(The writer is a senior journalist; views expressed are personal)