A review of Anita Nahal’s Kisses at the expresso bar ekphrastic prose poems, Kelsay Books, USA, 2022, and Kiriti Sengupta’s water has many colors, Hawakal Publishers, New Delhi, 2022

A picture can speak a million words and a poem can create a million pictures, this fact has been amply borne out by both books that have over the last few weeks, made me see the world in its many hues.

The authors wear several hats. Anita Nahal, is a poet who also writes flash fiction and books for children’s along with being a D&I consultant, professor & higher education administrator. She has the writing gene in her as she is the daughter of the famous Chaman Nahal ‘Azadi’ remembered most for his book Azadi. Nahal has included him and her mother Sudarshna in her dedication to the book. Kiriti Sengupta is a qualified dentist which probably accounts for his winsome smile! And he is a poet in English and Bengali as also a translator and editor. As publisher (Hawakal publications), he has created a real niche for creative writing, especially for poetry that provides a platform for upcoming or new talent.

Kisses at the expresso bar is a collection of ekphrastic prose poems. Anita Nahal draws upon the greek ‘ekphrasis’ as a literary device to provide a detailed description of a work of visual art. The art work is by seven artists from across the world using diverse media and some who use mixed media. It is difficult to see what came first, the text or the image- there is such a symbiotic relationship between the two. The first image that greets one is a pair of eyes from the author’s personal collection. Haunting eyes, they seem to have an x-ray vision and carry within their depths so many stories of things seen, moments felt and memories that linger. The eyes are striking and carry a wealth of wisdom, a wealth of knowing and also of unknowing and a craving to know more which Nahal calls intriguingly, ‘The eyes of valentine’. Was it the priestly knowledge of St Valentine or was it only a reference to the all-encompassing gaze of love that a valentine must have that Nahal meant? Perhaps both. And another ‘eye’ that one soon comes across is ‘Eye of the storm’ with the visual by Lorette C. Luzajie from Canada. Medical vocabulary is enmeshed with representations from literary works. The eyes are the windows to the world and determine how we respond to it; both picture and word picture effectively convey this fact.

The sculptures and paintings by Elizabeth ‘Lish’ Skec from Melbourne that follow next are startling to say the least. Gender and nature are a focal point of much of Nahal’s writing and the prose poems that accompany the images by Skec as also others in this book often underline that. In the ‘Greatest warrior is metamorphic Mother Earth, for example, the picture is that of a headless and limbless figure resembling almost a suit of armour, although composed of leaves in different shades. Nahal’s opening lines are so apt, ‘Petals adorn my broken self and like our ancestors I search for yarn and fable in each’. This again resurfaces in the image and prose poem entitled, ‘Half woman, half-empty’, drawing upon the famous Beauvoirian dictum of "One is not born a woman but becomes one." Nahal asks pointedly, ‘Why is becoming full a gendered thing? Blimey!’ The intertwining of Nature and gender continues with the detailed thangka painting by Madan Tashi which begs the question by Nahal, ‘If Earth had not been a mother?’ Nahal busts our unquestioning acceptance and complicity with a gendered world in the ironic questions she asks in this piece. Madhumita Sinha’s paintings are also nature centric and her painting ‘The flame of the forest’ with its many colours makes the poet dewll on the colours of life and wonder if there is any room for escape as one finds ‘ between tree trunks’.

Not just in this book but across all of her writings, Nahal draws upon her experience of straddling different worlds, diasporas, communities and domains. Thus the visuals by Michael D Harris are accompanied by apt prose poems entitled ‘Haves and have nots’ and ‘Humdrum of my fabric’ that reflect the myriad experiences Nahal has in her multidimensional universe. The patterns of Manju Narain’s quit art are fascinating and the two shared by Nahal in which she looks at life, perhaps through these patterns to find a rhythm are like teasers; you want more!

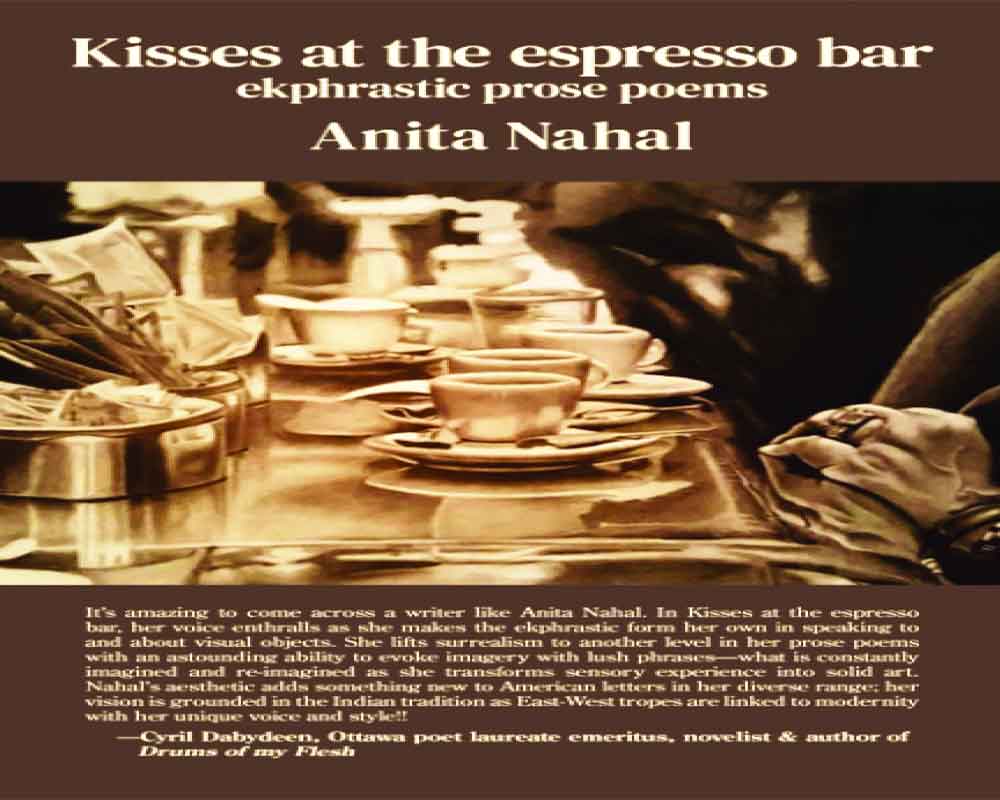

Nahal saves the most evocative images for the last section, those by graphite pencil artist, Anthony Grammond. The art work is so real that it is almost surreal; every fold of skin so skillfully drawn by this artist. The title piece, ‘Kisses at the expresso bar’ belongs to this last section and both the visual as well as the words will transport you into an expresso bar. You could almost taste the coffee! And if you do so, don’t forget to carry Nahal’s book with you to explore, slowly and deliciously with every sip.

Kiriti Sengupta, awardee of the Rabindranath Tagore literary prize, 2018, had curated a beautiful book of illustrative poetry and prose in 2020 called Shimmer Spring. The poems in that collection were rich with layers of meaning ranging from the political to the spiritual, nuanced observations of life with the most evocative illustrations. Sengupta is thus no stranger to iluustrative/ed poetry and the expertise tells in this volume, written entirely by him. The book entitled water has many colours is illustrated by Rochishnu Sanyal and like all Hawakal publications, is a treat to the eyes from the front cover itself, also by Sanyal. Despite Sengupta’s warning in ‘Why you should not buy a book’ (‘cover often deceives’), the Hawakal publications have covers as riveting as the contents.

The three lines in the opening poem (also the title piece), ‘Water has many colours, /smudging pebbles/along its path’ immediately have one pause to ponder on the nature of life itself and how each moment is so different from the other yet so interconnected. There is a ‘smudging’ effect that every lived second has on the next to give a sense of continuum, though each is only a ripple. Packed with meaning, like all of the poems in the volume, Sengupta wields his pen like a scalpel; he chisels out a feeling in the briefest of ways and yet makes one think about it endlessly. The next poem called ‘Santiniketan’ is acerbic to say the least. Almost nonchalantly Sengupta is incisively critical of the double standards/speak that one can perceive in all walks of life, entering even the halls of fame. This use of irony like a double edged sword persists in Sengupta’s writing. The sting is gentle but unmistakable in its sharpness.

Sengupta appears to be taken in by spaces and he sees in them potential for control and freedom. In ‘Home’, Sengupta conveys the sense that the home is a space that while sheltering an individual, also allows tremendous scope for the individual to take wings and fly that nest. It is a poem that will resonate with creative artists in particular who may feel anchored to their home and yet are aware that their creativity cannot be shackled to any moorings. In some ways, the poem ‘Memoir’ too carries echoes of the same perspective. In ‘Line of control’, the poet brings out the familiar sense of territoriality which accompanies those who share places. The visual by Sanyal accompanying the poem is perfectly apt and captivating.

The poem by Sengupta that held this reader’s attention is called ‘Troth’. In the shortest and simplest way possible, he speaks of the fears that a married Bengali woman has regarding her husband and how zealously she guards her shakha and pala since it is considered a bad omen if they crack. Superstition, tradition, love, rationality, lies are all woven together in what seems like a challenging of the notion of love. Again, in ‘Orison’, there is subtle subversion in the lines, ‘Elders exalt the esse of/her spouse/sada suhagan raho’. Sengupta uses almost a matter of fact tone to overturn patriarchal structures and tradition.

Nothing seems to escape the eagle eyes of this poet. And nothing stops him from articulating his views, fearlessly. Be it addressing the suicide of a Professor at Jadvapur University or the humdrum everyday (and the symbolism therein) in the seven poems called ‘Classic’, Sengupta will not let you drown in a sea of expressions. Rather, he will delicately prise your eyes open to the wonders of the sea in much the same way as one finds it magical while snorkeling.

Both these beautiful books of illustrated/ive poetry have underlined the fact that the world of mixed media is an artistic channel that those with creative abilities can use powerfully.

Swati Pal, Professor and Principal, Janki Devi Memorial College, University of Delhi, is the author of In Absentia, a collection of poems by her and Living on, a volume of poems she has edited. Several of her poems appear in anthologies.