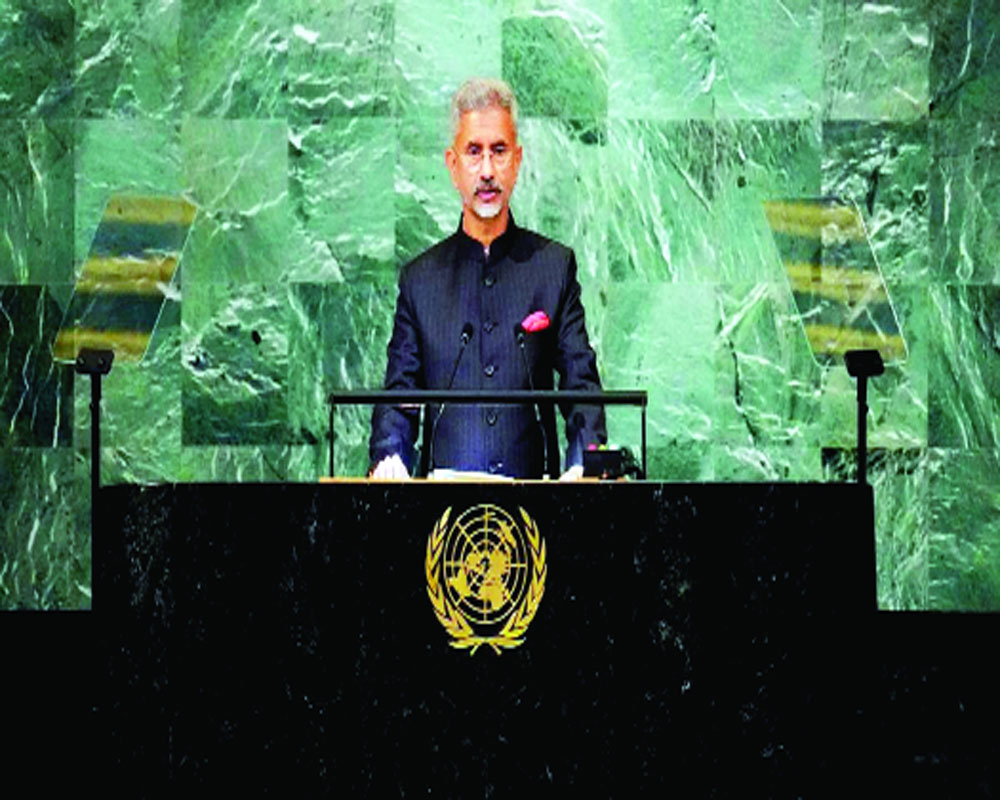

India has been airing the concerns of the Global South vociferously; S Jaishankar’s address at the 78th Session of UNGA was a case in point

India has tried to use consistently the forum of the United Nations not only in pursuing its foreign policy goals effectively but also in projecting itself as the advocate of the Global South. India’s leadership quality was demonstrated in the 1972 Stockholm Conference on the Human Environment which made it possible for the Stockholm Declaration to embody several principles that protect the interests of the global south. The legacy of Stockholm carries even today when India’s External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar raised the issue of climate change, mobilising resources for sustainable development goals and reforming multilateral development banks at the 78th session of the UN on 29 September 2023.

This has to be seen in the context of the New Delhi Declaration of G20. The declaration set the direction of future negotiations on important economic issues including climate financing which has for the first time put a $5.9 trillion figure to green financing requirements for developing countries, reforms in multilateral development banks, international taxation and sustainable development. Although this new green financing requirement does not generate legal obligations for the developed north, it amounts to underlining very clearly that in the context of urgency of restricting global average temperature below 1.5 degrees as compared to-industrial level, financial needs will have to enhance over and above 100 billion dollar mark. The requirement of mobilising 100 billion dollars per year by 2020 is the obligation on the part of the developed north.

India as an Advocate in the Context of Climate Change. One agenda item that India has used to position itself as the advocate of the global south is the issue of climate change. The latter is not only a serious environmental challenge but is also a serious economic and developmental concern, which also directly impinges upon realizing the goals of sustainable development. India’s contribution is least in the creation of climate change but it is placed to bear the brunt likewise of many developing countries more. India used its coalitional reach of the global south that the developed countries are historically responsible for climate change and their per capita emissions of greenhouse gases are very high as compared to developing countries. In addition, the developed north is financially and technologically capable of playing a lead role in dealing with the challenge of climate change.

India’s arguments relating to climate change galvanized adequate support of the global south in enshrining a regime of differentiation in the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). The idea of differentiation expressed through the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities (CBDR) has been held responsible for warding off pressure by the developed north that the developing countries should also bear greenhouse gas mitigation obligations. The formulation of the principle of CBDR is being interpreted as an Indian formula that corresponds between the northern advocates of common responsibilities and southern proponents of a main responsibility of the developed north. Although the regime of differentiation has changed as it is reflected in the Paris Agreement on Climate Change 2015, it still guides many aspects of climate change and the environment, especially the transfer of finance and technology from the developed north to the developing south.

Mr Jaishankar touched upon lifestyle for the environment in his speech at the UN, which is not rhetoric but is grounded in a reasoned argument. This is an affirmation of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s introduction of the mission of “LiFE (Lifestyle for the Environment)” at the Conference of the Parties meeting of the UNFCCC. The lifestyle for the environment is aimed at engaging individuals in mitigating the adverse effects of climate change. In other words, it is also about developing long-term environment-friendly habits. India’s lifestyle for environment argument is aimed at curbing and underlining the overconsumption lifestyle more found in the North than in the South. This argument is very close to the argument developed by noted environmentalists Anil Agarwal and Sunita Narain in their research titled Global Warming in an Unequal World. They argued in their work, which constitutes a centrepiece of the argument taken by the global south quite often during climate change negotiations, that there is a need to distinguish between “survival” emissions of developing countries and “luxury” emissions in developed countries.

The Energy and Resources Institute (TERI) shows that lower capita GHG emissions in India are not due to poverty alone, but also to more sustainable lifestyles than in developed countries. For example, CO2 emissions from the agricultural sector- from the field to the table- are about 0.1 tons CO2/million calories in India against 1.7-2.2 tons in developed countries, inter alia due to a less meat-based diet. CO2 emissions from transportation per passenger kilometre are 16 grams in India against 118 and 193 grams in the European Union (EU) and the US respectively.

This is an era when agriculture systems worldwide are in search of sustainable cropping to deal with existing issues of malnutrition, food insecurity, resource depletion, climate-resilient crops, and environmental problems associated with agriculture, millet is a new tool for India which fits in well with India’s efforts in strengthening its narrative of lifestyle for environment.

(The author is a senior Assistant Professor in International Environmental Law at the Indian Society of International Law, New Delhi; views expressed are personal)