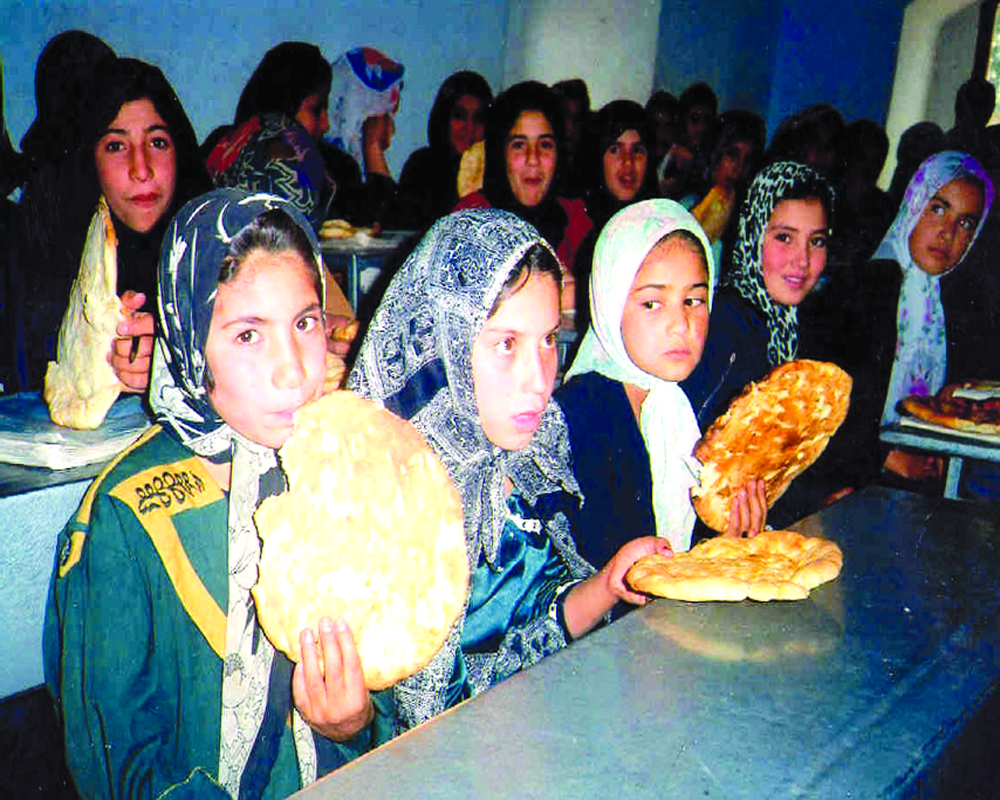

Apart from the dread, hunger and lack of nutrition are gnawing at the Afghan people

It is time to strike a balance between terror and hunger in Afghanistan. Millions of lives are at stake as the UN organisations involved in relief activities say food stocks may last not more than a month in the vast rural stretches. Hunger and lack of nutrition are the bywords as the country’s economy is in a downward spiral. Essential commodities are already out of stock in urban stores. Scarce vegetables are selling at double the prices. Panic buying in the aftermath of the Taliban takeover on August 15 cleaned up shelves in stores with no replenishing. Flour and oil are already out of limits for the poor. In the villages, the situation is worse as families are falling back on grain and wheat stored for future crops. Drought and famine have anyway hit the country for the umpteenth time. The risk of displacement adds to the pangs of hunger for a large section of the population. The fighting before August had made over 600,000 Afghans flee homes. The UN agencies estimate that around 3.5 million people are internally displaced. At least 10 million children, a sizeable section of them malnourished, depend on humanitarian assistance just to survive. The UN’s World Food Programme has said many Afghans did not have access to cash to afford sufficient food. That is because banks had closed down after August 15. The Taliban are now negotiating with banks for re-opening branches. However, they have set a cap on weekly withdrawal of $200 to avoid a run on banks.

Afghanistan’s economic experts, now in exile, insist that the situation will lead to a weaker currency, faster inflation and capital controls. Most civil servants have not been receiving salaries for months. Many more claim they have suffered pay cuts as high as 75 per cent since the Taliban took over. There is no indication that the Taliban are bothered about the dire straits. No proactive economic decisions have been forthcoming. Their contribution has been limited to appointing an obscure official to head the central bank to address the crisis. Little is known about his actions. The Taliban cadres though appear unfazed as it is rumoured that there is enough drug and opium money in their coffers. They are currently embroiled in internal squabbles that appear to have worsened after the interim set-up was announced. The Taliban are preoccupied with settling an existential debate — their Achilles’ heel, actually — between their urban political face and orthodox armed command represented by Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar and Khalil-ur-Rahman Haqqani, respectively. The question is whether the Taliban are playing a blinking game with the rest of the world, holding the latter responsible for restoring economic order. Do they await the international community to pour money into rehabilitation works? Or expect it to recognise their interim governance apparatus? That is linked to lifting the freeze on Afghan assets worth billions of dollars; only a recognised government can take control of the funds.