For artist Ganesh Haloi, working on a piece is like cultivating crops on a part of land. It’s the reason why nature’s true essence can be found in his works, says Uma Nair

Man needs colour to live; it’s just as necessary an element as fire and water,” said the great Fernand Léger in The Aesthetics of the Machine, Geometric Order and True (1923).

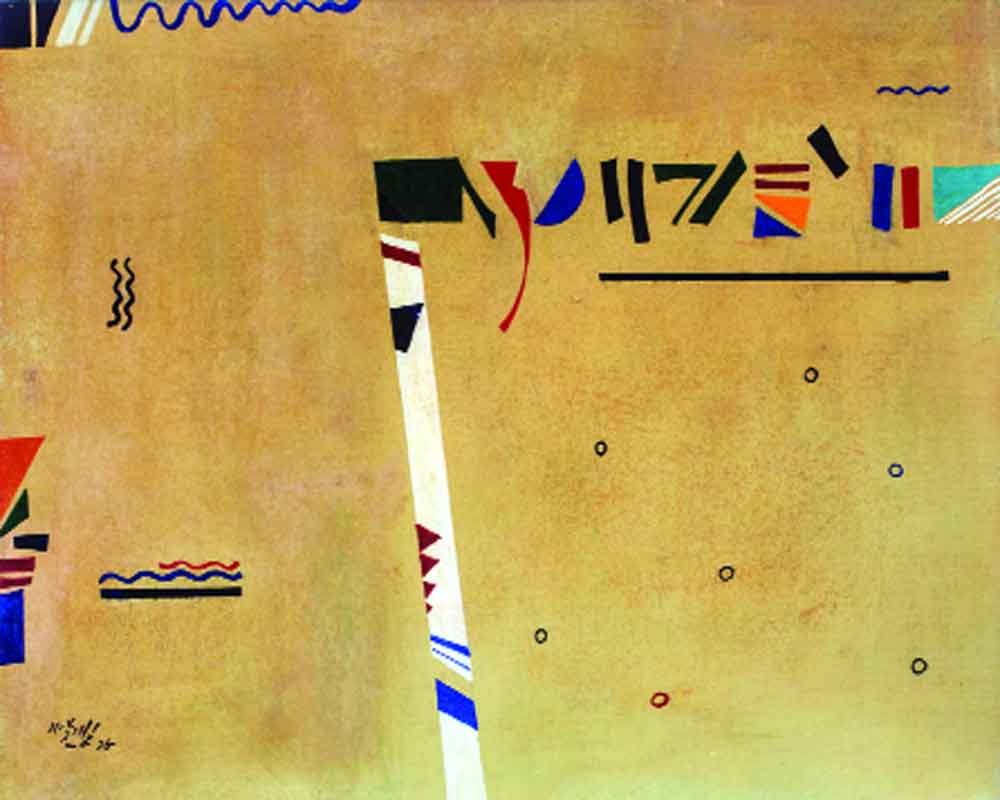

The quaint and curious little space at the Akar Prakar Contemporary, showcasing minimal colour field landscapes by the great master from Bengal, Ganesh Haloi, reminds one of this. Haloi has been brought into the limelight by director Reena Lath. His solo will be unveiled at the Asia Art Week, New York in March.

In these landscapes, the modernist you see suffuses fertile pastures tinted by tiny strokes of colour, the splendour of which, all of a sudden, transforms into a bouquet of earth songs. It’s one of the reasons why Haloi was handpicked by Documenta 14 curator Adam Szymczyk in 2014.

Tranquility of colour fields

Haloi plays with the tranquility of colour fields as he creates a study of his homeland, which is intense, in-depth and unexpected. In one of them, one could spot a golden yellow rapture, while in another, a vigorous tenor of mud brown. One can also find a voluminous ochre that could belong to a paddy field or an autumnal evening in Shantiniketan. Whatever the case maybe, Haloi creates a counterpoise, aptly balancing space and volume.

In a life that has found the graceful gravitas of pure abstraction, Haloi’s works at Akar Prakar are both joyful and dynamic. In 2006, at his home in Kolkata, he said in an interview, “Colour is not just a vital necessity in the hands of an artist. It is like a raw material, which is primary as well as essential in life. It is like air, water and fire. If I am thinking of my experiences and memories, I cannot imagine it without the mood of the atmosphere. When you look at a pond, at the plants, fishes and birds around you, you are also thinking of all that is natural in colour tones. When we look at nature in its purest form, we are recording what is linked to light. The memory becomes an intensity which we can either strengthen or soften. This process for me is the abstraction that I engage in.”

Fragmented homogeneity

His tiny strokes look as though light is vibrating and moving along the rhythms of the wind. Musical breadths and deeper understandings of abstract expressionism — all come into play in Haloi’s works. He is a scholar, who is content to create something within the orbit of his own oasis. He is the reflective traveller content within the conventions of time and space and happy to venture into terra incognita. His canvases speak a language, where each portion takes on a novel, fresh and moving meaning.

One morning in 2006, in the silence of his flat and company of artist Sudip Roy, Haloi said, “A work of art is like a land I cultivate. It grows progressively but quietly. Abstraction is neither a technique nor geometry. It is born of one’s own residue of memory and experience. The stories, events and spectacles I saw in my childhood come back to me. The sadness of the Bengal famine and the helplessness of people, engulfs me. The sunset at the pond in the village... everything accumulates as associations with the past. When I put paint to paper or canvas, I want to create something that is fresh and full of the sap of fertility. Like the poet who sits down to write, I gaze at my canvas or paper for some time. Yes, I want the trigger of a vital energy and a zest. The beginning is quiet but once the first swish of the pliant brush or the pen touches the canvas, it flows. Some stimulus must accumulate within me so that I can create the unexpected symphony. It’s like one of the compositions from the Gitabitan — moody, rhythmic and full of resonance. That resonance must happen.”

When asked if he likes to be alone when he paints, Haloi said his wait in front of his canvas or sheet of Nepali paper is a combination of silent patience and the gesture of poise. These landscapes are tinged with grace and dreaminess, populated by strokes that resemble the rustling of leaves or just riverine tributaries, bathed in harmonies of green or tan or an indigo. They are rooted in the ethos of his own world.

In the density of depth and the melody of motion, Haloi’s exhibition is a paean to poetic patterns, prismatic haikus that lull the senses long after we have gone through an immersive experience of dulcet tunes of the yesteryear. It would be intriguing to know how New York responds to India’s resonant master even as he brings alive the words by Aldous Huxley: “There are things known and there are things unknown, and in between are the doors of perception.”

(Form & Play will be shown in New York at the Fuller Building from March 12th to 19th.)