Had the Government chosen consensus-building over confrontation with regard to the farm Acts, things wouldn’t have come to such a pass

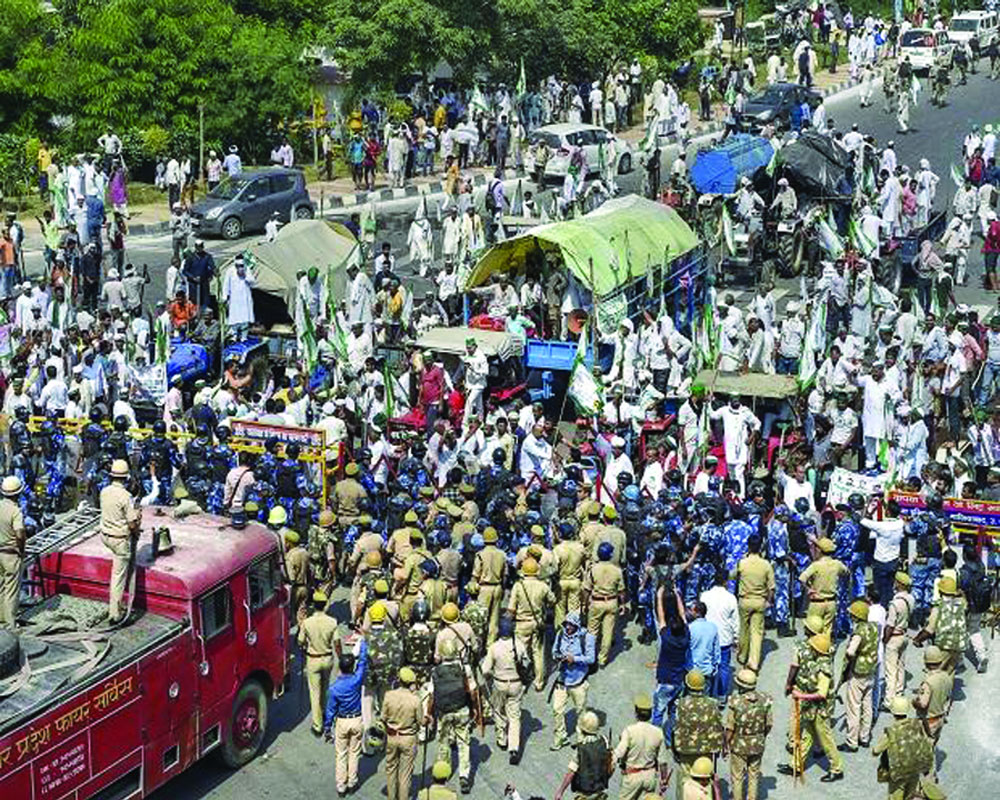

The big question is could the farmers’ march, as it manifested through the dramatic visuals of a surge of protesters fighting teargas, demolishing barricades and facing water cannons, have been avoided in COVID-stressed times? Would they have been driven to such desperation if the Government had given them a decent listen and the Agriculture Minister had not absented himself from a conciliatory meeting on the recent farm Acts? And at a time when stubble burning is compounding the pollution and pandemic crisis across Delhi-NCR, should not that have been the point of discussion first? Honestly, the Government could have managed this better, considering that it was well aware of the farmers’ grievances and should have attempted to reassure them. Instead, in its stubbornness to show it can push necessary reforms, it refused to engage with them and gifted the Opposition an agenda to beat it with. It may want to show the farmers and the Opposition in a poor light but beyond political point-scoring, who gained what, except for being exposed to a large super spreader risk? For the Government may claim that these laws will help farmers get better prices for their crops and allow them access to wider markets but the latter are wary of the corporatisation implicit in these Acts and argue that they could be cheated out of a fair price. Yes, structurally, the laws may seem to streamline agricultural processes but the farmers are not willing to give up their right to exist on their terms. Worse, they fear that these could ultimately reduce the current system of open-ended FCI procurement by the State. Besides, they feel that entering into contracts with corporations would willy-nilly give the latter negotiating rights and greater control. And that although the older system would continue, as a weakened parallel mechanism, it would ultimately crumble before emerging monopolies. They cite how contract farming failed in the sugarcane sector with farmers chasing dues that are owed to them in crores. Of course, there’s the case of PepsiCo suing farmers in Gujarat that showed the latter’s vulnerability in the face of big corporations. State Governments like Punjab are obviously upset that access to another market would dry up their own revenue from their Agricultural Produce Marketing Committee (APMC) mandis and are seeing this as an affront to federal controls. The fear that market yards would be abolished is largely unfounded though, considering the eNAM platform connects thousands of them across 18 states and three Union Territories (UTs). But then the Government has also not tried to be educative but confrontational. It is the devil in the detail that has our farming community up in arms. For example, a licence won’t be required to trade in farm produce and anyone with a PAN card can now buy directly from the farmers “outside” their geographical area. Farmers want clarity on what “outside” means and contrary to perception that they want the middlemen out, they actually have a trusted bond with their existing commission agents as the latter’s licence is proof enough of credibility and delivery abilities, and they would not want to experiment with an untested model. Besides, they want direct payment and not through banks, which could deduct amounts as loan recovery.

The opposition to farm laws could have been avoided had the Government preferred a Standing Committee scrutiny over pushing the law unceremoniously with a voice vote in the Upper House. A GST-like consensus involving Centre and States would have helped. But there was no attempt at consensus-building, no dialogue with the farmers’ unions, State Governments or the Opposition parties. Since agriculture-related issues come under the State List in Schedule VII of the Constitution, the Centre should have consulted federal governments. One just had to look at the playbook of the Atal Bihari Vajpayee Government on the contentious issue of contract farming, which was envisaged in the National Agriculture Policy, 2000. Instead of bringing a Central law, it circulated a Model Agricultural Produce Marketing (Regulation) Act to the States for adoption in 2003. The ensuing UPA-I government continued the policy. Contract farming was included as an option in the National Farmers’ Policy, 2007. By August the same year, 15 States had brought amendments in the APMC (Regulation) Acts based on the model legislation. The intransigence on the farm Acts is in contrast with the Government’s handling of the recently enacted labour codes. Although these had some controversial provisions too, since they reduced 29 existing labour laws into four legislations, there was not much hue and cry as they were vetted by the department-related Standing Committee of the Lok Sabha. Yes, there is a need to reform agricultural marketing in the time of food surplus. But care should be taken to ensure that the farmers are legally protected in what is still an unequal deal. If only the Acts came with the caveat that no trade transactions would take place below the notified MSP, the farmers could have been easily pacified. Many experts would argue that it is easy enough to push reforms in a sector that anyway makes a very small portion of our GDP. But farmers make up 60 per cent of the country’s population, a voter base that no political party can ignore. Certainly not States like Punjab and Haryana, which are heavily dependent on procurement at MSP.