Australian photographer John Gollings portrays buildings as living, ageless habitats rather than monuments which are lifeless. By Chahak Mittal

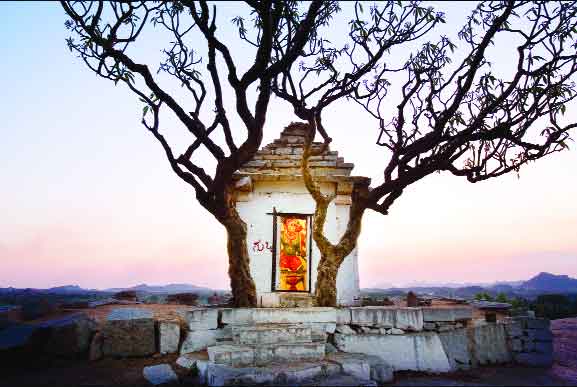

As one entered the pavilion that showcased an array of Australian architectural photographer John Gollings’ works, a variety of large canvas-like photographs spoke volumes about the maestro’s years of endless wandering through the tribal and rural streets of India. Capturing the greatest works by artisans and architects, the photographs make it seem that the audience is almost visiting the places all across the world. But it is Hampi in India which had Gollings’ attention as he had covered the town with its various abandoned structures, which are now being listed under the archaeological sites of India.

However, the photographer feels that such masterpieces shouldn’t be forgotten, rather should be revived and preserved for generations to come. They are an evidence of the various cultures and traditions that rulers and kings followed. They shouldn’t be taken for granted or abandoned and should be regarded as major monuments and symbols of the rich Indian heritage.

Gollings’ exploration and documentation of both modern and ancient sites in India has resulted in a body of work that records its changing social, economic and political landscape. “These projects are of great cultural and historical significance. Their value should be kept intact,” he said.

Be it the architecture across Asia, the abandoned Chinese city of Jiaohe; the Khmer temples of the Angkor Wat, stretched across mainland Southeast Asia; the architecture of the Hindu Vijayanagar Empire; the grain stores of the nomadic Berbers in Libya; or the abandoned structures in Hampi, Gollings has brought his characteristic style, giving the viewer an understanding of the embedded perspectives in each of the captured structures.

It was in 1980 when Gollings had first visited Hampi and fallen in love with and developed admiration for the place. Ever since, he has been returning to the site every year.

Explaining his innate fondness of Hampi, the photographer said that the town is “vast” and its monuments are “an architectural splendour.” He said that even though he has had been visiting the place regularly for so many years, it doesn’t leave a stone unturned in surprising him each time. “I discover a new aspect every time I come here, which is why I have become so fond of it. I am addicted to Hampi. I have gained a vast experience in architectural photography here as the sites give me a chance to experiment in many ways. I am able to give an aesthetic touch to it by taking photographs in different lights and times of the day. There cannot be any other archaeological site like this,” said he.

He complained that ironically, ever since the place has had been listed in the world heritage sites, “it has become difficult to work here. It was much simpler and beautiful before. Now there are fences all around the place and timing that limit my visits. It is closed for visitors after five in the evening.”

His photographs, that were recently displayed at the India Habitat Centre’s Photosphere and also as part of the six-month long Australia Fest, were a classic example of time travel, with capsules featuring architectural changes.

The exhibition also showcased his most recent project for which the photographer went around capturing step wells in India. He said that these are all examples of modern architecture. “They say a lot about traditionality and history of Indian temples. When I am capturing a building, I want it to stand out. Earlier, when Indian temples were captured in black and white, their colours would lie on the same page. But here, I wanted to make each colour stand out. Hence, these step wells with muddy look describe perfectly what architecture offers to traditions,” he explained.

Fashion might go out of style or change with time, but buildings and structures remain timeless. As an epiphany, the photographer said that it occurred to him that he “wanted to capture everything that had ever been built in the world.”

For him, it’s all about taking and waiting for that “one perfect shot.”