The Mahatma’s impact on social transformation has been indelible. Yet, his true legacy is in shreds. There’s a lack of understanding of his beliefs today

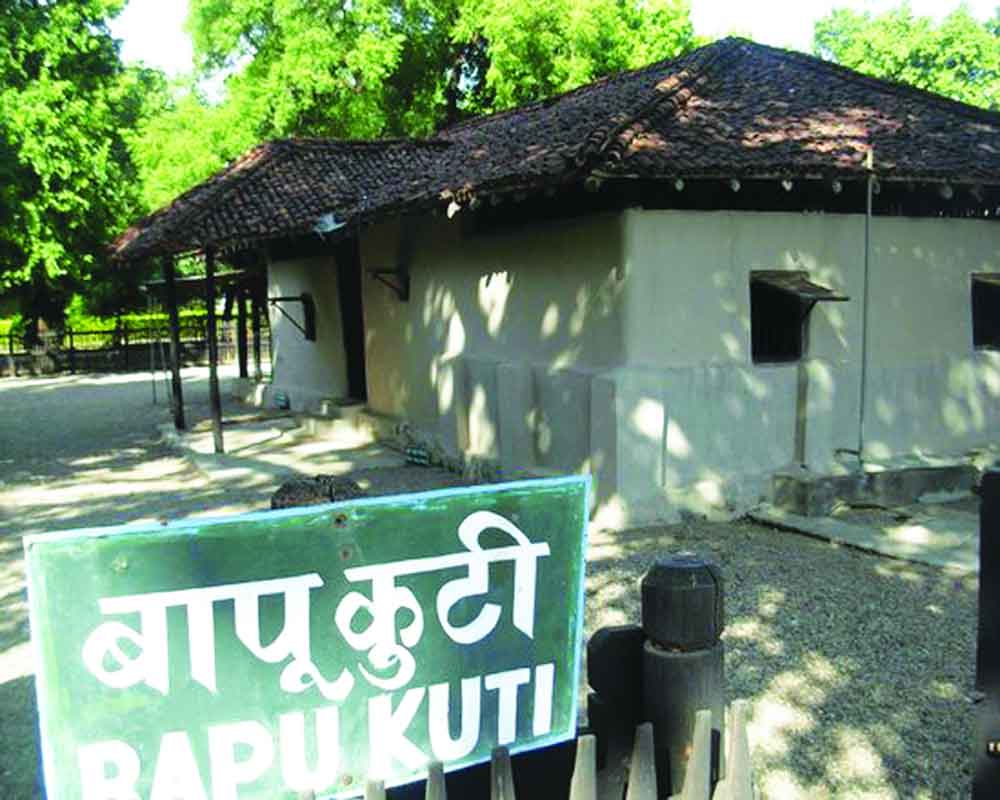

Eighty kilometres to the east of Nagpur lies Bapu Kuti, a historic site in Sewagram, the “village of service”, nestled in the serene rustic surroundings close to the Wardha district. This was the humble abode of Mahatma Gandhi from 1936 to 1948 and was the epicentre of the Indian freedom movement. During the 12 years Gandhi lived here, Wardha became the de facto nationalist capital of India. A motley array of foreign delegations — politicians, pacifists, religious leaders and do-gooders of all complexions — regularly found their way to Sewagram. In July 1942, the Quit India resolution was passed here and in 1946, Gandhi left the ashram, never to return.

By 1931, Gandhi was already famous. He had travelled to Europe, where he had drawn eager crowds and journalists and where he had met a roster of the famous and the powerful that included the British monarch, Benito Mussolini, Charlie Chaplin and Romain Rolland. Gandhi wrote to Jamnalal Bajaj, an Indian industrialist, a philanthropist, and Indian independence fighter, that he wanted to live alone in a hut in a small village. However, his presence alone was enough to draw scores of votaries as well as visitors from across the country and around the world as Jawaharlal Nehru came several times. Soon, there was a road and one hut became a cluster. The British set up a telephone so that they could communicate with the Mahatma. However, Gandhi’s attempt to disconnect from the world failed just like his attempt to change India from outside did. It, however, did quicken the course of the trajectory towards independence.

One does not have to be a Gandhi devotee to be able to appreciate the austere beauty of the ashram’s premises. Gandhi shared these thoughts about who should consider residing in it: “He alone deserves to be called an inmate of the ashram who has ceased to have any worldly relation — one involving monetary interests — with his parents or other relatives; who has no other needs save those of food and clothing; and who is ever watchful in the observance of the 11 cardinal vows. Therefore, he who needs to make savings should never be regarded as an ashram inmate.”

Bapu Kuti is nothing short of a museum. A quaint bath, an elderly, dignified telephone box and neat little alcoves shyly peeping from the walls, all serve to create an inexplicable nostalgia for a past that we were not even part of. There are some bare relics: Glasses, a spoon, a pocket watch and a pumice stone to scrub his body. The kitchen contains the flour grinder Gandhi put to use occasionally. His cot and massage table have also been retained. The sacredness of the place is preserved by the several sombre trees that have themselves withstood the passage of history and ravages of time. The practice of daily prayers in the open continues. The campus glows with humility evoking memories of its master.

The structures were to be simple enough for a small group of ordinary people to build and maintain on their own. Indeed, the modest scale of the lodgings comes as a surprise to many visitors. The cottages are well-crafted with thick mud-brick walls, clay roof tiles and palm leaf thatching. The most important of these historic structures are Adi Niwas, Ba Kuti and Bapu Kuti. Adi Niwas was the first house built at Sewagram and was the place where the first ashram members lived together. Bapu Kuti and Ba Kuti are the cottages of Mahatma Gandhi and his wife, Kasturba Gandhi, respectively.

Originally determined to live in an isolated hut, Gandhi decided that his own house should be open from all sides in order to let natural elements and his visitors circulate freely. The building’s design, though loosely inspired by traditional village houses, was an idealised design from Gandhi’s imaginary village “in my mind” as he wrote in his famous exchange of letters with Nehru in 1945.

Bapu Kuti is a sparse and austere mud-walled cottage. The building remains as a symbol of the Mahatma’s dedication to a mode of living that treads lightly on the land and is accessible in its material simplicity to even the poorest. Three of Gandhi’s original possessions are highlighted in the building today: His iconic round-shaped spectacles, his pocket-watch and his two cross-strapped slippers. These three have taken on a symbolic value in the commemoration of the great leader. The first enabled him to see the world around him with clarity and the second helped him keep and respect time — that of others as much as his own — and the third symbolised his light but unmistakable footprint on the Indian landscape.

A number of Gandhi’s other sparse possessions are exhibited at Bapu Kuti: A walking stick, a portable spinning wheel, a paperweight, an inkpot, a pencil stand, a bowl, prayer beads and a small statue of three monkeys among other things. The cottage is partitioned into separate rooms, which left some space for Gandhi to write, meet visitors and for guests to sleep. It also contains a latrine connected to a septic tank with a note informing visitors that Gandhi cleaned it himself. Bamboo shelving hangs from the ceiling for storage. For aesthetic effect, Mirabehn herself drew simple ornamental designs on the walls of palm trees, an “Om” symbol and a spinning wheel.

The food was also prepared according to rule number four of Gandhi’s (Sabarmati) ashram rules. According to Gandhi, the first step to control sexual appetite — that is essential for curbing one’s selfish impulses — was to eliminate the pleasure of eating: “Food must, therefore, be taken like medicine under proper restraint.” Fischer noted in his diary that he didn’t like the mush that was served and after the third day, he declined to eat any more of it.

The peace of village life was bittersweet. Sewagram’s calm was, in fact, due to the absence of any real, living activity. Today, the ashram is preserved in time in the manner of an old sepia photograph but the idealised life it documents is now dead. Sewagram is no longer a vibrant place inhabited by the indefatigable Gandhi and his devoted votaries. It is a shell of what it was, a time capsule fondly and painstakingly preserved but devoid of its living inhabitants and shorn of its original aura.

The site is at once stimulating and soothing, haunting yet peaceful. It is as if the aura of the man himself hovers above it. Part of the reason, of course, is that the ashram simply doesn’t attract that many visitors as Gandhi’s importance and pertinence to ordinary Indians fades.

Gandhi had warned in 1928 that if India took to industrialisation after the manner of the West, “it would strip the world bare like locusts.” We disregarded him and adopted energy and resource-guzzling technologies rather than seeking more sustainable alternatives. The results are there for all to see. Many of our rivers are biologically dead. The chemical contamination of the soil is immense and possibly irreversible. Sewagram continued to nurture Gandhi’s vision of a sustainable world.

Gandhi infused India with a revolutionary blend of politics and spirituality. He called his action-based philosophy satyagraha or the truth force. For Jawaharlal Nehru, the defining image of Gandhi was: “Many pictures rise in my mind of this man (Gandhi) ...but the picture that is dominant… is as I saw him marching, staff in hand, to Dandi on the Salt March in 1930. Here was the pilgrim on his quest of truth, peaceful, determined and fearless, who would continue that quest and pilgrimage, regardless of consequences.”

Gandhi’s impact was indelible. He guided India to independence and forced his countrymen to question their deepest prejudices about caste, religion and violence. His ideas continue to resonate across the world and he has inspired generations of great leaders. As Einstein summed up in his tribute: “Generations to come will scarce believe that such a one as this ever in flesh and blood walked upon this earth.”

Yet the true reality is that Gandhi’s legacy is in shreds. It had already started waning immediately after his death. His vision of villages as the most fertile ground for India’s progress now seems like a utopian dream. The Governor-General of independent India, C Rajagopalachari, gave a disenchanted verdict in the years that immediately followed Gandhi’s death. It still rings true: “The glamour of modern technology, money and power is so seductive that no one — I mean no one — can resist it. The handfuls of Gandhians, who still believe in his philosophy of a simple life in a simple society, are mostly cranks.”

(The writer is Member, NITI Aayog’s National Committee on Financial Literacy and Inclusion for Women)