Aseem Bhargava discovers Stretched Terrains, a set of seven independent and yet interconnected exhibitions on display at the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art

A country and nation in flux — ever expanding, redefining its ethos and finding its feet through a journey which is both ever continuing and yet stationary in its meaning. The underlying theme of the exhibition is to marry and bring together the post-independence decades and display across disciplines — be it architecture, painting, film and the written word in many forms — about how the creative process is the bedrock of making the country one whole.

The juxtaposition of works by the three artists from the Progressive Artists Group, founded in Bombay in the late 40s, is what sets the pace for a voyage, which is nomadic in its execution and still brings us together as a people, rooted in their habitat and adobe.

The works of MF Husain, SH Raza and FN Souza bring together themes of the home, country and roots, moving and movement through an individual and personal investment and yet so different in their scope. Husain, through works like Yatra and Peeli Dhoop, presents us with what he did so well, connecting us with the true India, a pastoral which was immediately and quintessentially Indian in its scope.

In his 13 drawings of Mumbai, Husain presents us with typical kitsch symbols, especially those of the Hindi film industry, all displaying cheerful co-existence, in a time when life was much simpler and fissures of the coming decades were not a worry, as became the reality later, in a city torn by violence, terrorism and communal differences.

Other works by Husain, including one that is eponymous to him — no prizes for guessing, horses — convey strife. The feeling of violence is palpable and real. Ganga, a 1973 work, moves away from the typical depiction of it, but a cow amongst other symbols is so contemporary, keeping in mind today’s realities.

The Black Sun and Raza, the bindu, which was the leitmotif of the artist despite living in Paris for 60 years, needed to constantly return to his roots of the sal tree forests and his roots in Mandala in Madhya Pradesh. His terrain may often and ever so consummately capture Europe, in its clean stark depiction, but was always generously littered with the culture of his country. In this exhibition too, ever so often a village, a riverside, a view of Malabar Hill and Indore bazaars pop up which speak of a simpler, rural India, meandering gently, like the Rehwa or Narmada, on whose banks he was raised by his father, a forest officer.

An idyllic time, when the foundation of much of the Indian terrain was being changed by the leaders of a young nation, is juxtaposed and reflected in the photos of Delhi. In collaboration with Ram Rehman, we witness the transformation that architects like Kuldip Singh, Raj Rewal, Habib Rehman, JK Chowdhury, Joseph Allen Stein and AP Kanvinde were bringing to their modern temples of both administration and learning. None as poignantly at display, as the exhibition shows us, like the pictures of the Hall of Nations, which as a remnant, outlived its purpose. As the curator Roobina Karode notes in her foreword and it strikes you almost immediately in the choice of paintings and photographs, some will not be able to withstand change and with ebbing relevance, will be gone. A milieu, once used and popular, will one day be only a memory and a picture, which needs to be captured and kept.

Interesting to note, that only one, the Gandhi Memorial Hall, finds place in the legendary Madan Mahatta’s pictures, as all others are well post the Nehruvian era, i.e. late 1960s to almost the 90s. This was soon to give way to a more modern sensibility supposedly. Then there’s the Punjabi Baroque, which came to be the mainstay of a Delhi in a hurry to be recognised as a “world city.” It has come to lose its aesthetic sensibility, albeit slowly with time.

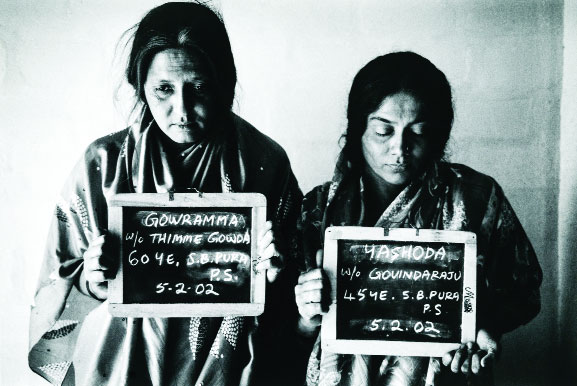

The section which Atul Dodiya, Mithu Sen and Pushpamala pepper with their own individual tributes and homages to ideas, which mildly border on fantasy, as Pushpamala does with such compelling theatrical ability and Sen with her fragile renditions, are indeed what grab your attention and show why artists today are reinterpreting the known.

Dodiya pays tribute to many a master with their personal stamps strewn across the cabinets which contain them. In his other offering, the curious interplay between the debt that we owe to MK Gandhi and his lead role in our Independence struggle and the evolving European art movement is indeed an entirely new sensibility.

Mithu Sen, in her distinctive style, gives us Bhupen Khakhar and imbues delicacy, an inevitability that Khakhar often brought to his men, using a gaze which was and in even 2017 remains somewhat veiled, with a harsh truth being presented in a ghostly fashion of their own beings. Notable that she captures so well the dark humour, almost vapid, which Khakhar’s figures at times displayed. Though he was arguably one of the bravest artistes, who brought through his art an unflinching truth, which was personally his own too.

It’s indeed fitting that this is followed by Pushpamala N, who indeed is almost a rarity in today’s landscape. Her unwavering ability to grasp, pick up, mildly mock and laugh back at us as a collective people make her ask us, “Why are we NEVER amusedIJ” And this is where she scores.