The essential aim of any theory of punishment is, or should be, to reduce crime in society. We are failing as a nation to address this issue

Justice delayed is justice denied,” is an old English adage which rings just as true today. For some like Machang lalung, who spent 54 years in prison without trial, it’s a poignant reminder of our failure as a society.

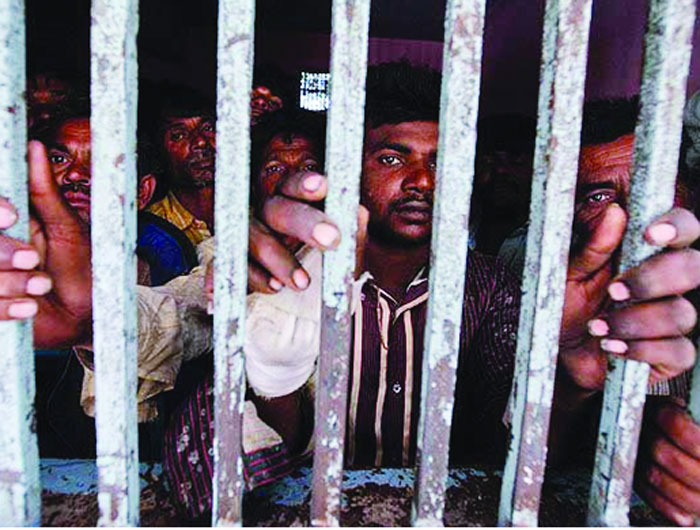

The numbers: According to the report published by Amnesty International India tiledJustice Under Trial: A Study of Pre-trial Detention in India which examined data available with the National Crime Records Bureau and data that was available with the organization, for the past ten years the percentage of under-trials compared to the total number of prisoners in Indian jails has almost consistently been over 65 per cent. This is a frightening statistic, with our numbers only marginally better than Pakistan but significantly worse than countries such as Uzbekistan. A breakdown of the individuals that make up this astonishing figure is even more worrisome and warrants examination. It cannot be ignored that the same Amnesty International report states that of the total number of undertrials in India, 53 per cent are Dalits, Muslims or Adivasis. This is a staggering figure considering that these communities only make up 39 per cent of India’s total population. Another number that caught my attention was that 42 per cent of the undertrials have not completed their secondary education. This is not particularly surprising as the communities mentioned are some of the poorest in India. Cold statistics, though revealing, have a tendency to dehumanise the suffering that each of these individuals goes through for years on end.

Numbers don’t lie and there seems to be overwhelming evidence that people from certain communities and from poorer backgrounds tend to be on the receiving end of the inefficiencies of our judicial system. This sentiment is echoed in the 268th report of the law Commission, which states that “it has become a norm than an aberration in most jurisdictions including India that the powerful, rich and influential obtain bail promptly and with ease, whereas the masses/the common/the poor languish in jails.” The reasons mooted behind the exceptionally high number of undertrials in our country are numerous such as a dearth of legal-aid lawyers who are extremely poorly paid and are, therefore, unwilling to undertake bail cases on behalf of the marginalized or a lack of understanding of the law by police officers on the ground who actually enforce the laws. I have attempted to examine some of these issues later in this article but it is without doubt that we as a country need to examine the ethos that governs our penal system.

Theories of Punishment: Theories of punishment are the rationale behind punitive action against an individual in a particular manner. There are a variety of theories of punishment, however broadly they may be classified as:

- The deterrent theory which primarily believes that severe punishments can help ensure that criminals don’t repeat the crime;

- The retributive theory which is premised on vengeance and seeks to punish an offender and ensure suffering;

- The preventive theory which focuses on preventing crime rather than deterring an offender or ensuring vengeance; and

- The reformative theory which seeks reform the offender through individual treatment and seeks to make the individual a law-abiding member of society.

The essential aim of any theory of punishment however is or should be to reduce crime in a society. Ideally, a modern society seeks to not only reduce crime but also to ensure that individuals are transformed into contributing members of a society. However, the Indian Penal Code, which is the primary penal statute in our country, was drafted at a different period of time in our history. It was a legislation that sought to enforce the authority of a brutal Government rather than to ensure the well-being of its oppressed subjects. Therefore, punishment under the IPC and the judicial interpretation that has followed primarily seems to be heavily influencedby the retributive theory and the deterrence theory but has been found lacking in terms of the reformative theory. This is unfortunate as more and more countries are realizing that the way forward is not a theory that isolates an individual from society but one that helps the individual become a contributing member of it.

What can we doIJ Smarter men than I have spoken about what steps can be taken to help reduce the severity of the issue at hand and there is no doubt that structural reforms are required. However, even if the cure treads a long and trying path, there are a few palliative measures that could be considered.

Prosecute laddering: An issue that plagues the policy system is that of laddering. This is whenpolice ‘inflates’ charges in a particular case. For example, a charge of assault (which is not a very serious charge) is twinned along with an attempt to murder charge (which is much more severe charge). Such practices need to be discouraged and it is important police forces are audited on the grounds of whether the charges that have in reality been placed on the accused were warranted. Currently, the superintendent of police and the deputy superintendent of police are the individuals who are responsible for ensuring that such practices are not taking place while charges are being drawn up. Therefore, in the event police officers are found guilty of engaging in such practices, it is imperative that the guilty officers and the supervising officers should be held accountable for their misconduct.

Investigation techniques and a focus on career criminals: Criminals are typically of two types: career criminals who are repeat offenders and have made crime a way of life such as dacoits etc. and non-professional criminals who typically do not have a history of violent conduct or of breaking the law. The Indian police system however treats both such offenders the same way. This leads to a situation where most of the crime which is carried out by career criminals is not given adequate focus and also unfortunately leads to a situation where a criminal who has committed a one-off offence is forced to spend most of his or her life in prison. Granted that there are certain offences that may warrant this treatment such as certain offences against the body; however, to treat all these criminals the same is counterproductive and harmful to society. In my opinion, the police should focus a greater percentage of its resources on career criminals rather than the odd person accused of a crime. The bail system in India should reflect this approach as well. Furthermore, there is an overreliance in our system on oral evidence as opposed to scientific and forensic evidence. This is a massive problem as judges cannot rely on objective, scientific evidence that is placed before them to adjudicate on a case and instead they are forced to rely on oral testimony, which is more often than not severely contested. This leads to a longer trial period for the accused. There must be a much greater focus on teaching police forces modern investigating techniques and encouraging police to build its case and frame charges by placing a greater reliance on scientific and forensic evidence rather than mere oral statements.

Compulsory bail: Currently the manner in which the bail system works under Indian law is that in the case of bailable offences, bail is required to be given to an offender as a matter of right. In the case of non-bailable offences there is an impression that bail is to be granted as an exception rather than as a rule. However, the law prescribes that bail in the case of non-bailable offences may be granted unless, inter alia, certain circumstances as prescribed by the law have occurred. One such exception is if the person has been convicted previously for an offence which is punishable by death or imprisonment for life or if such person has been convicted on two or more occasions of a non-bailable or cognizable offence. Therefore, even the letter of the law seems to intend that bail should be granted as a matter of right. In reality, this is not the approach that has been followed. It may then be useful to further clarify the law and explicitly state that bail must be compulsorily given unless there are certain exceptional circumstances or if the accused in a repeat offender or a career criminal.

I have carried some of these issues with me since my time with the Indian Police Service and later as a citizen of the country. I hope some of these concerns resonate with you as much as they did with me.

(The writer, Jharkhand PCC president, is a former MP and IPS officer. Views expressed are personal)