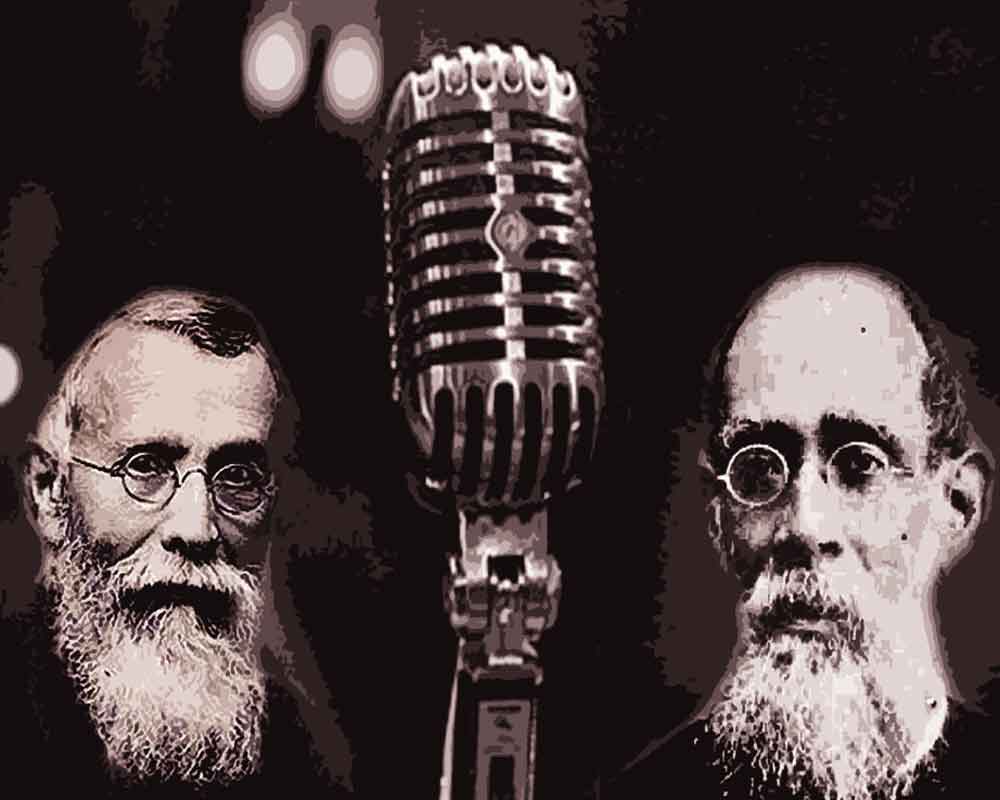

Oratory or speechmaking emerged as a powerful medium of mass communication and political agitation in India since the middle of 19th century. The epoch made leaders out of speakers. But it was not simply their ‘gift of the gab’. There were groundbreaking technological and academic advancements that aided the orators, writes PRIYADARSHI DUTTA in his new book, The Microphone Men. An edited excerpt:

On May 26, 1877, Surendranath Banerjea embarked upon a rail tour of northern India. He was the first Indian political leader to take advantage of an expanding railway network. His tour revealed how a new public life was unfolding in North-Western Provinces (the present day Uttar Pradesh), two decades after the 1857 uprising had mauled its plains. His immediate objective was to popularise the protest against lowering of maximum age limit in civil services examination. The Secretary of State’s decision was aimed at practically excluding Indian aspirants from the civil services. A resolution against the move had been adopted at a large public meeting of Indian Association at Town Hall of Calcutta on March 24, 1877. Banerjea was selected to represent the cause in northern India. It was his idea to take the civil services agitation beyond Bengal. He felt the cause had potential to unite Indians politically. The tour vindicated his expectations.

Banerjea’s journey over the spine of the East Indian Railways took him till Lahore, the Capital of undivided Punjab. He addressed at least two crowded public meetings there. He also helped establish a Lahore Indian Association. It was closely modelled upon the original Indian Association, founded by Banerjea and Ananda Mohan Bose in 1876. Downstream, he halted at Amritsar, Meerut, Delhi, Aligarh, Lucknow, Kanpur, Allahabad, and Varanasi. Wherever he went, he addressed crowded public meetings and interacted with the budding intelligentsia. He also catalysed the formation of several political groups on the lines of the Indian Association. The civil service memorandum was endorsed everywhere. But, more importantly, the tour revealed possibilities of civilian politics.

Banerjea’s tour was path-breaking. It presaged the synergy between the railways and the civilian leadership. The railways liberated the orators from their provincial limits, and catapulted them on the national stage. The railroads facilitated the civilian leadership to come together and exchange notes. In 1878, Banerjea travelled to Bombay and Madras presidencies in pursuit of civil service memorandum. He met Vishwanath Mandlik, KT Telang, and Pherozeshah Mehta in Bombay. In Poona, he was the guest of Justice MG Ranade. In Madras, he met Dr Dhanaketu Raju, Chensal Rao, and Humayan Jan Bahadur etc. He met the leading men of the city at Pacheappa Hall in a conclave. The nucleus of Indian leadership was thus being created.

The railroads also took the leaders to new audiences. A Bengali could find an avid listener in Punjab; a Parsi could enthrall the audience in Calcutta; an orator from Andhra could charm the audience in Amraoti. This was how new national heroes emerged towards the end of the 19th century. The heroes of this era did not come on horseback with flaming swords. They travelled mainly by train and wielded the microphone, figuratively speaking.

The Indian National Congress could not have materialised without the benefit of the railways. In the circular notifying the first Congress at Poona between December 25 and 31, 1885, the delegates were advised to reach Poona railway station. The Poona Sarvajanik Sabha, organiser of the Congress, made arrangements from the railway station to the venue, Peshwa’s garden near Parbati Hill. The sudden outbreak of cholera, however, prevented the gathering in Poona. The Congress had to be shifted to Bombay.

The railway, by its very nature, promoted a civil society. In the pre-railway era, horse was the fastest means of travelling. But the bulk of those beasts were employed in aristocratic occupations like warfare, pageantry, riding, and hunting. The demand was so great that Mughals had to import Arab and Persian horses from the Middle East. The animal was hardly open to regular civilian or commercial use.

The Turks had subjugated India rapidly on dint of cavalry. Conversant with the use of stirrup, they unleashed the true potential of cavalry warfare in India. From being an assault wing of the army, horses had become a constituent of the power structure. The power pyramid of the Mughal Empire was built on the horses. The rank and pay of commanders was consummate with the number of horses they commanded. Bernier speaks of Omrahs — or power elites — holding titles like hazary, douhazary, dehhazary, which meant lord of 1,000, 2,000, and 10,000 horses respectively.

Cavalry predominated in the Maratha army under the Peshwas. From Shivaji,

who employed mostly infantry, the composition tilted heavily in favour of cavalry (with supportive artillery) under the Peshwas in the 18th century. It was a definite sign of the Marathas going expansionists. No wonder they rapidly conquered territories from the Mughals, who were in terminal decline. The great era of cavalry was put to an end by the British in the Third-Anglo Martha War in 1818. The British crushed the freebooters called Pindaris, who acted as the irregular cavalry of the Marathas.

The horse-borne empires in India had retained speed as an exclusive domain of the military. Public life, consequently, was crippled and stunted throughout the medieval age. A commoner in India was largely a pedestrian. He might occasionally ride the bullock cart or palanquin. Both were symbols of tardiness. Planned journeys over longer distance were not possible. Travellers often sojourned for weeks, months and even years together at a location. The normal business of their life thus remained suspended for that long.

The railway came as Promethean Fire for the lesser mortals. It delivered speed to the civilian population. The poor were found lining up for cheap tickets of third class. The trains ran as per a notified time table. This made planned travels the new norm. Post and telegraph services aided the process.

Let’s say Banerjea, sitting in Calcutta, could apprise his hosts in Lucknow or Poona about the date and time of his arrival there. The schedule of his speech could thus be confirmed accordingly. He could leave the station on the morrow of addressing a public speech there. Perhaps in 10 days altogether, he could return to Calcutta from another end of India after addressing a few public meetings. One could travel without seriously disturbing the normal business of life.

The year-on-year growth in human and cargo traffic was phenomenal since the mid-1850s when the railway began its operations. By the late 1870s, the network had attained a critical mass. By the end of 1879, or 25 years after the railways being introduced in India, some 6,128 miles of railway tracks had been constructed by the companies at an expense of nearly £97,872,000.

Banerjea was fully conscious of the importance of the railways in unifying India. He articulated it in a speech at Calcutta’s Town Hall in March, 1878. “The distance between Calcutta and Delhi is not 1,400 miles but only a question of 44 hours. The distance between Calcutta and Lahore is not 1,600 miles but only a question 52 hours. The distance between Calcutta and Bombay is not 1,900 miles, only a question of 61 hours.” Naturally, with the advent of diesel and electricity engines, the duration of travel reduced. But Banerjea could still cover enormous political ground with the aid of steam engines. It helped consolidate the Indian public life.

Statistics was another factor that enriched oratory. Figures invaded the domain of facts in the speeches and writings by Indians in the 1870s. Dadabhai Naoroji was the pioneer in the field. In his paper titled ‘England’s Duties to India’ read before a predominantly British audience at East India Association, London, on May 2, 1867, he accused Britain of exploiting India economically. He built his case on a wealth of data. An excerpt from the paper illustrates the point.

In the shape of ‘home charges’ alone, there has been a transfer of about 100 millions of pounds sterling, exclusive of interest on public debt, from the wealth of India to that of England since 1829, during the last 36 years only. The total territorial charges in India since 1829 have been about 820 millions. Supposing that out of the latter sum, only one-eighth represents the sum remitted to England by Europeans in Government service for maintenance of relatives and families, for education of children, for savings made at the time of retiring, the sums expended by them for purchases of English articles for their own consumption, and also sums paid in India for Government stores of English produce and manufacturers — there is then another 100 millions added to the wealth of England. In principal alone, therefore, there is 200 millions, which at the ordinary interest of 5 per cent, will now make above 450 millions, not to say anything of the far better account to which an energetic people like the English have turned this tide of wealth. This in addition to the wealth of England of 450 millions is only that of the last 37 years. Now with regard to the long period of British Connexion before 1829, the total territorial charges in India from 1787 to 1829 amounts to about 600 million. Taking only one-tenth of this remittance for the purpose mentioned above, there is about 60 million in principal, which with interest to the present day, added to the acquisitions previous to 1787, may fairly be put down for 1,150 millions.”

Did it sound like a mathematical dissertation to his audience? They should have known that Dadabhai was previously a professor of mathematics. He turned trade, economics, and finance into important factors of political discourse. But wherefrom he might have sourced these figures? Actually, he left the answer in the speech itself. He attached four appendices of tabulated data to his paper. These were based on Parliamentary Returns of Indian Accounts. He also relied upon the Second Customs Report, 1858.

In his speech at the Bombay Presidency Association held on September 29, 1885, Dadabhai said: “Here are a few figures which will tell their tale. The income of the United Kingdom may be roughly taken at £1,200,000,000 and its gross revenue about £87,000,000 giving a proportion of 7½ per cent of the income. Of British India, the income is hardly £400,000,000 and its gross revenue about £70,000,000 giving 17½ per cent of the income, and yet Sir James tells the English people that the people of India are not heavily taxed, though paying out this wretched income, gross revenue of more than double the proportion of what the people of the enormously rich England pay for their gross revenue.

“They do not understand yet that their greatest interest is in increasing the ability of the Indians to buy their manufacturers. That if India were to buy a pound worth their cotton manufacturers per head per annum, that would given then a trade of £250,000,000 a year instead of the present poor imports into India of £25,000,000 of cotton yarn and manufacturers from all foreign countries of the world.”

Dadabhai was gifted in the matter of figures. He leavened his speeches with statistics. But they were not classroom lectures. They were actually lucent with his political humanism. His essays and correspondences, however, were heavily statistical. This was perhaps done consciously. A listener might lose interest in a heavily statistical speech, but a reader could revisit and re-examine the statistics at leisure. Dadabhai turned price rise, wages, taxation, tariff, rents, lending rates, agricultural output, industrial production data, import and export figures, and currency exchange rates into political talking points. His exposure to British political debates, besides his pedagogical background, made him ideally suited for the purpose.

Excerpted with permission from Priyadarshi Dutta’s The Microphone Men: How Orators Created a Modern India; Indus Source Books, Mumbai, Rs 799