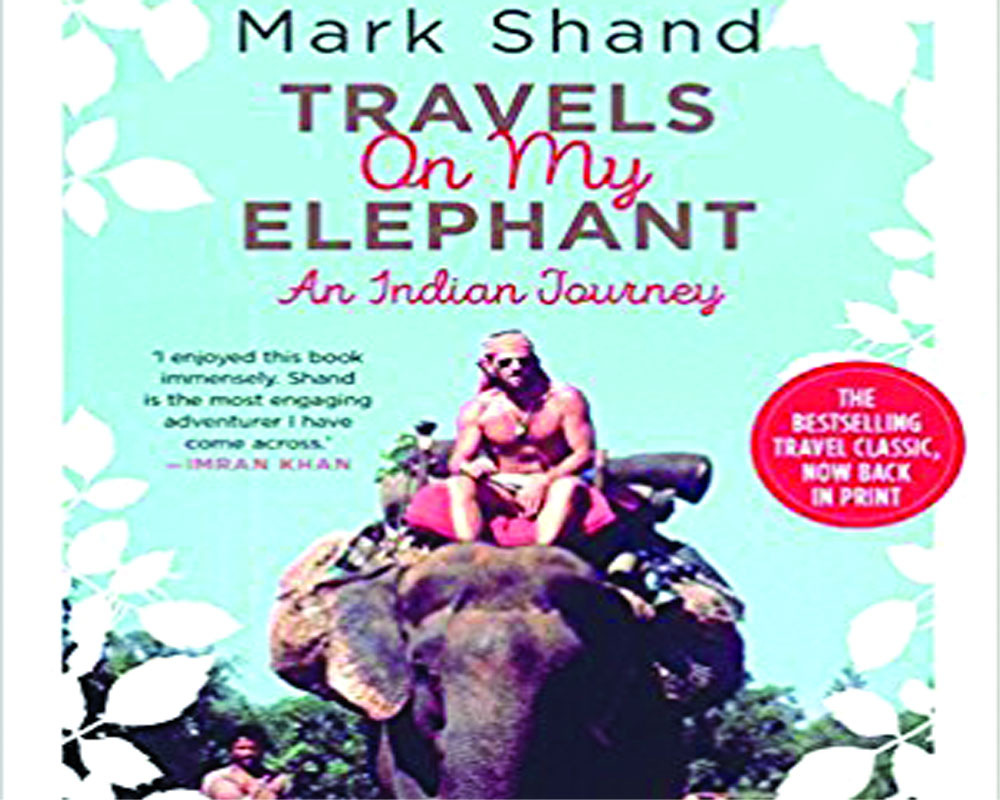

Travels on My Elephant

Author - Mark Shand

Publisher- Speaking Tiger, Rs 299

This book shows how author Mark Shand made a case for Asian elephants — the gentle giants who were struggling to survive in India, writes Gautam Mukherjee

Mark Shand, overflowing with an endearing, if aristocratic, noblesse oblige, British upper class, was the late brother of Camilla, Duchess of Cornwall, the future queen of England. After an epic journey through rural Odisha, as newly trained White mahout, atop his female Indian elephant, christened Tara, he wrote this wonderful book that captivated the world.

It was published first in 1991, became an iconic bestseller, won Shand the Travel Writer of the Year Award. It became the purpose, via his charity, Elephant Family, which evolved from this journey, of the rest of his relatively short life. It is however a toss-up between being a book about travel, camping, rivers, ponds and architectural monuments on the way, and the relationship between Shand, his educated Marathi companion Aditya, his frequently drunk mahout teacher Bhim, a couple or three other assistants, Gokul, Idrajit, Khusto, and the very expressive thirty odd year old elephant.

The elephant, in particular, scrawny, under-fed, injured from ill-fitting leg irons, is rescued by Shand when he buys her for Rs 1,01,000 when that meant 4,000 pounds sterling. There is also some of an Englishman’s musings over the onward progress of a beloved former colony, a patchwork of social and cultural history, and amusing anecdotes and conversations with the people Shand met along the way. Of course, he keeps saying how well everyone, particularly in officialdom, treats him and his entourage. And well they might, given his own eminence, that of his exalted friends, and the officials, including the police, tasked to help him along the way.

Through it all, there is a genuine eagerness to learn, contribute, and share, that sparkles through the narrative. This was one Raja-Sahab, who wasn’t afraid of laughing at himself and the sight he presented. There he was, stripped to the waist, bandanna on head, rocking on his cushioned howdah, callused and bleeding bare toes used to steer the elephant from behind its ears. Shouting out bravely, doing the best he could with Hindustani mahout commands.

From a life of begging and party tricks, going largely hungry for half the year when it wasn’t being used at weddings, Tara gradually develops an unmistakable mischievousness, dignity, and grace under the ministrations of Shand.

Time and again Tara escapes, particularly when being given a bath, and has to be coaxed back with the intuitive moves suggested by Bhim the senior mahout, sometimes, even after going AWOL for a night or two. And so, they travel, at a pace of perhaps four miles an hour. Mark Shand, died in 2014, at the age of 63. But before he passed on, he had already raised more than 10 million pounds sterling to help the survival of the Asian elephant, under pressure from growing urbanisation and destruction of its habitat. The money has been used, mostly in India, to relocate and resettle people living in the jungle and to facilitate the creation of elephant corridors so that the pachyderms can move about freely from one protected forest to another. It all began with the journey described most engagingly in this book. A progress through rural Odisha, from near the Sun Temple at Konark, facilitated by current Chief Minister Naveen Patnaik, a personal friend of Shand’s, to the elephant fair at Sonpur in Bihar.

At the Sonpur Mela, both master Shand, and Tara the elephant, by now deeply loved by Shand, are terrified at the prospect of selling Tara. Providentially however, Shand is able to gift Tara to the Wrights, old India hands, of Tollygunge Club fame, who were at the fair because they needed an elephant for their resort and reserve, Kipling Camp in Madhya Pradesh.

Shand kept tabs, and went, more than once, to visit Tara, whom he credited with saving his “life”, presumably from the pursuit of non-stop hedonism. He is recognised by the elephant and finds her well looked after, content, every bit the pampered princess. “She wakes up, eats, sleeps, swims, has a massage, eats and then goes back to bed-day in, day out”.

It is not as if Mark Shand did not try his hand at various adventures. He went to Bali to sail a yacht to retrace an old romance starring a WWII pilot called Tyler, who settled with many apsara-like local wives on an island called Renill — but unfortunately in the face of a typhoon. And then, there were travels on the moody Brahmaputra.

But in retrospect, it is animal conservation — mainly the Asian elephant, that became the nub of Mark Shand’s lasting contribution. The relevance of this book, even 23 years after it was first published, was brought home by a recent news report on six elephants rescued by the authorities, two of them quite ill, being used illegally in Delhi by people who rent them out for weddings.

It is, as if, nothing has changed for elephants ever since heavy machinery and tanks put them out of their primary business. Gone are the days when they moved logs, though they still might be doing so in Asia Pacific rain forests. But certainly, the days of Hannibal and Porus and their war elephants is long gone. Now elephants are used in temple processions in South India, weddings all over the country to symbolise the God of new beginnings, and to amuse tourists.

Taking in elephants out of such servitude however, is easier said than done. Each elephant needs at least 1.25 acres of space, and lakhs of rupees to look after. They need specialised feed and care to thrive. To send such urban elephants back to the wild, apart from posing transport problems, needs a period of gradual psychological rehabilitation as well. Still, there is work that must be done urgently.