Women seem to have been the main focus of the master artist’s creativity. His representations depict the dynamic of their changing relationship with a male-dominated environment

KG Subramanyan, who left for the hereafter in 2016 at the age of 92, was an artist working with multiple media, besides being a scholar, teacher and intellectual who also wrote verse, sometimes reflecting a deep angst and, more often, with his tongue in his cheek and wit — sometimes acerbic — on his sleeve. His fame, as is widely known, rests on his art which constituted a massive, varied and evolving corpus — drawings, paintings, terracotta sculptures — reflecting his deep insights into the human condition under an over-arching moral universe marked by an eternal conflict between benevolent and malevolent forces, which also raged within individuals.

His art mirrored not only the states of vulnerability, helplessness, submission and defeat — as well as those of strength, rebelliousness, determination and triumph — into which the conflict led human beings, but the latter’s search for pleasure, joy and happiness distilled from events of quotidian life. In sharp contrast to the puritanical abhorrence of the human body, he depicted it in its diverse manifestations from the beautiful to the ugly as well as its many postures induced by emotions within, which were also reflected in facial countenances, particularly the expression in the eyes.

One sees all this in his artwork featuring in the exhibition titled “Women Seen and Remembered: Drawings by KG Subramanyam (1953-2016)” staged by Art Heritage and spread out in two spaces — Shridharani Gallery and Art Heritage — at the Triveni Kala Sangam in Delhi. Curated and designed by Amal Allana, director of Art Heritage, the exhibition comprises approximately 250 works from the Seagull Foundation for the Arts and The Alkazi Collection of Art. Of these, the ones from the former will go back to it at the end of the show.

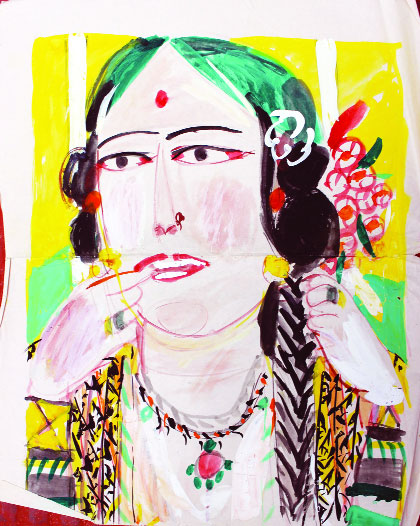

The exhibition has a special significance in terms of Subramanyan’s work as women seemed to have been the main focus of his creativity, accounting for more than 50 per cent of his drawings and sketches. Understandably, his perception and representation of them have been evolving, a phenomenon clearly discernible in the chronologically-arranged exhibits spread over roughly six decades — which also depict the dynamics of their changing relationship with their male-dominated environment. Thus, from the pliant, submissive and domesticated beings depicted through the slumped and drooping postures of their bodies in the 1950s, they are transformed in the 1970s into an unabashedly flirtatious individuals aware of their selves and proudly displaying their blossoming sensuality with scarcely-concealed sexual undertones.

One sees another change in the 1980s and 1990s when women appear wearing, or preparing to wear, masks. One wonders whether it was to meet on even terms men who are also seen wearing masks. Or were these meant to be devices to show to different people the aspects of one’s self that one wanted to show them? The tendency is global and extends to the deeper exercise of changing one’s face itself. It will be interesting to recall here the following lines from TS Eliot’s The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrok: “There will be time, there will be time/ To prepare a face to meet the faces that you meet;/ There will be time to murder and create,/ And time for all the works and days of hands/ That lift and drop a question on your plate..”

The idea of preparing a face or wearing a mask to meet faces and masks indicates an autonomy of intent and signifies a certain coming of age, a certain desire and ability to negotiate with the world on one’s own terms. Post-2000, the woman is depicted as a shaper of event, destinies and discourse. She is Durga the goddess with 10 arms, each holding a weapon, who slays Mahishasura, the Buffalo Demon. Durga, is also a manifestation of Parvati, wife of Lord Siva, who also appears in other forms such as Uma, Gauri, Bhairavi, Ambika and Kali, the latter an awe-inspiring presence in black in the Hindu pantheon who rules over Time, Change, Power and Destruction.

Subramanyan showed women as having the same strengths and attributes as goddesses by depicting them in close proximity of the latter. Viewing the progressive unfolding of his presentation of women and their growing self-awareness, assertiveness and consciousness of their sensuality, one wonders whether this was a result of his encounter with the movement for gender justice and women’s bodily integrity that emerged and grew in strength over the same period. This writer has not encountered any writing on the subject. He must, however, have been familiar at least with its broad contours — given his focus on women and responsiveness to the social and political currents of his time. The latter aspect of his concerns was manifest in the display of his political works in the exhibition “Seeking a Poetry of the Real” (also curated by Amal Allana) by Art Heritage in collaboration with The Seagull Foundation for the Arts” in 2017, the 40th anniversary year of the founding of Art Heritage in Delhi in 1977 by Ebrahim and Roshen Alkazi.

Taken together, the two exhibitions provide an informed and enlightening view of the works of a master creator whose passing has left a void that will continue to be deeply felt.

(The writer is Consultant Editor, The Pioneer, and an author)