We know Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel as someone who, after Independence, integrated this country of 500-odd princely states into one. But we don’t know much about Patel, the father — who loved his son but never allowed him to come closer to the corridors of power, and how his daughter lived and died in penury but never compromised her integrity

Not long ago, before families came to control parties and their heads began to plot the rise and sustenance of their wards in politics in India, lived one of the country’s most powerful men who placed the country before family and self. He had the stature to get his children into positions of power, of influence, of long-term financial security. If he had wanted, they could have exploited his political legacy during his lifetime and after his death. It was not to be, because that man was Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel.

It sounds unbelievable in an age that we live in today, when the wife takes over the reins of a state — almost like the state is her family’s kingdom and the people are its beholden subjects — when the incumbent Chief Minister and her husband is jailed, and vacates the position after he is freed. It appears ridiculous in an era where the father, after having had a good time as a Chief Minister, lets his son occupy the position just so that the chair remains in the family — and never mind that the young man has absolutely no inkling of governance and proceeds to make a mess of his coronation. And, it is clearly incongruous in a time when the country’s oldest party — one which Sardar Patel had incidentally been associated with — has been run by a dynasty beginning from mother to her son to her daughter-in-law to her grandson — and who knows the granddaughter may get officially added in time to come.

Were Sardar Patel to come alive today, he would be appalled by this state of affairs. He would be ashamed to see that political parties, which represent the collective will and wisdom of the people, should be owned and manipulated by a handful of people because they are privileged to have been born into the ‘right families’. He would be shocked to know that the blatant promotion of kith and kin does not even raise an eyebrow, let alone a public protest, anymore. In anguish, he would have told these brazen proponents of distribution of political patronage among sons and daughters and brothers and sisters and uncles and aunts and in-laws, who exploit the very same democratic system which was supposed to empower the weakest among the weak and not the strongest among the strong: ‘Enough or I shall die yet again!’

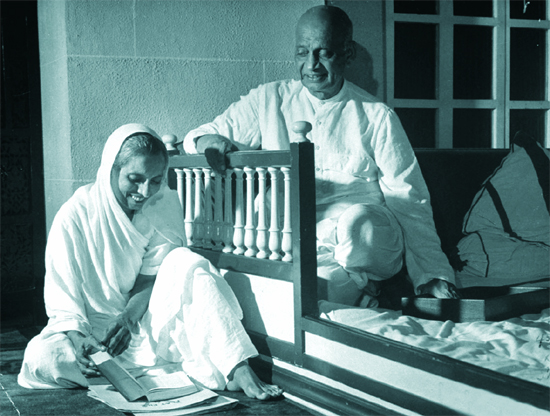

It’s not that he did not care for his two children — son Dahyabhai Patel and daughter Maniben Patel. He loved them so much that he kept them, or tried to keep them, away from power politics as much as he could. He knew that, upright as the children were, they could be victims of smear campaigns by unscrupulous elements. Worse, they would be used as baits to target his fair image and undermine national interests. It was the last which concerned him most.

Given the Sardar’s inclination, it’s not surprising that there is so little by way of published material which deals at length with the story of his two children. Yet, the little that there is, at least in the English language, offers enough insight on the Iron Man’s attitude towards them and his resolve to keep them at arm’s length from politics. Although he did not fully succeed in Dahyabhai Patel’s case — the son went on to become a reasonably successful Member of Parliament — he ensured that Dahyabhai remained largely away from the centre of power, in Mumbai, where the young man had also established a fairly prosperous business.

This is indicated from the following statement that Professor Hari Desai, in his capacity as the director of the Centre for Studies and Research on life and Works of Sardar Patel, once made: “Sardar’s politics was sacred. He always wanted his son Dahyabhai to be away from the corridors of powers, as he had a feeling that industrialists and others would exploit his relations with the Deputy Prime Minister.”

Sardar Patel’s concern that his position could be exploited by dubious elements who could reach out through his son, is further reflected in an instance which noted author Rajmohan Gandhi gives in his book (arguably the most definitive biography on the Iron Man), Patel: A life. Gandhi says that Dahyabhai arrived in Delhi to seek Sardar Patel’s permission to exchange a Karachi-based company the latter had acquired in 1945 for land left by a Muslim who had gone over to Pakistan. Gandhi writes, “The possibility that his son might seek or receive a favour in the capital incensed the Sardar, who ordered Dahyabhai to return to Bombay.” The noted author then goes on to quote what Sardar Patel told industrialist GD Birla: “Anger rose in me. I told him (Dahyabhai) he was going to get me out of here.” There were many similar instances.

Contrast the Sardar’s conduct with that of the patronage that today’s ministers and lesser politicians give to their wheeling-and-dealing relatives. It is futile to try drawing a list of the scams involving such examples, because it will take ages to be complete.

Can one imagine that a son of a Deputy Prime Minister should be asked to vacate his flat, and his father refuses to intervene, instead counselling the son to be reasonableIJ Rajmohan Gandhi cites Sardar Patel’s response when he heard that Dahyabhai had been ‘stiff and cold’ in his dealings with others on the issue. The Sardar wrote to his son: “There is nothing to be gained in speaking harshly or offensively... Do not make enemies... At one time my nature too was harsh. But I have felt a lot of remorse over it. I write to you from experience.” The situation is different today. We have sons and daughters holding on under some pretext to prime residential plots allotted in the name of their illustrious parents, as if they have the fundamental right to do so. Quite a few politicians are said to routinely grab property, directly or through their cronies. But Sardar Patel did not even intervene to ensure that his son retained a small flat.

If the Sardar kept his son on a tight leash, he did not have to strain this much with his daughter, Maniben. Deeply devoted to her father, Maniben did not dabble in politics although she, like her brother, had been a part of the freedom movement. Nor did she seek to exploit her position. In fact, she was completely unconcerned about her own future well-being, leading the doting father to once write to her that she must do something for herself. He wrote in December 1944, as Rajmohan Gandhi reproduces in the book, “The thought keeps coming to me that my time in this world is nearing its end. How long can you stay with meIJ Thinking of the future, shouldn’t you settle down in a field of your choice so that you have no sudden difficulties to face when I am goneIJ”

Note here that Sardar Patel’s concerns were twofold: First, that Maniben had no companionship in life; and second that he had done nothing to secure her financially. If he had wanted, he could have seen to it that she was taken care of for life, at least in matters of money. But there was no way the Sardar would do that. He left no property nor did he leave any provision for his daughter. She had considerable challenges in the last years of her life. The Sardar would have cried on seeing his beloved daughter’s plight, but it is unlikely that he would have, even then, done anything that he considered against his principles.

Maniben to her last breath upheld the pride and dignity that was her father’s legacy. Verghese Kurien — pioneer of the White Revolution in the country — gives a moving account of her situation, in his memoirs, I Too Had a Dream. She told the author of an incident when she went to meet Jawaharlal Nehru after the Sardar’s death. She had taken a book and a bag which the Sardar had directed her to give Nehru. The bag contained Rs 35 lakh that belonged to the Congress. Nehru took them and thanked her. This is what Maniben told Kurien: “I thought he (Nehru) might ask me how I would manage now, or at least ask if there was anything he could do to help me. But he never asked.”

Nehru’s conduct should not surprise anybody, given his dislike for Sardar Patel and his own pettiness in such matters. But, what is noteworthy is that Maniben did not seek favours even at a time when she was orphaned and was struggling to make ends meet.

Kurien goes on to note: “After all, the sacrifices that Sardar Patel made for the nation, it was very sad that the nation did nothing for his daughter... When she was dying, the Chief Minister of Gujarat, Chimanbhai Patel, came to her bedside with a photographer. He stood behind her bed and instructed him to take a picture... With a little effort, they could so easily have made her last years comfortable.”

The writer is editor, Opinion Page, The Pioneer